From his eye-popping visuals to his global streaming strategy, J Balvin has always been the captain of his career. Now, with a new album, label deal and management team, he’s showing there are no limits for Spanish-language artists.

A few days before the Super Bowl, the usually affable J Balvin seems preoccupied. He’s barely speaking, quietly answering questions from a small crew of assistants and distracting himself with a round of Pac-Man. He systematically pulls the lever on a vintage arcade machine inside his sparsely decorated trailer at the Hard Rock Stadium, located just outside of Miami proper, while wearing a black hoodie emblazoned with the words “Made in Medellín.” Come Sunday, when the Colombian reggaetón star will perform his global hit “Mi Gente” during an explosive set by Shakira and Jennifer Lopez that’ll be watched by over 100 million people, he’ll wear the same one — a billboard for his own success.

The door to the trailer opens. “They’re here,” says Matt Paris, the young Colombian singer Balvin just signed to his new label, Vibras, which Universal Music Latino — Balvin’s main home — is in talks to distribute. Balvin, 34, opens a nearby Nike box and pulls out a pair of rainbow Air Jordans that he designed, which will be widely available this summer — the first time the sports brand has collaborated with a Latin artist on a shoe design, he says. “This is a big cultural deal,” he adds, and suddenly it’s as if the clouds in his head have parted. He starts to grin as he affixes his logo — a yellow smiley face with thunderbolt eyes — to his heel before popping over to the trailer next door, where he shows off his footwear to his pal Bad Bunny, also slated for a halftime-show cameo. Balvin ambles to the field, shaking hands and waving at Lopez’s young dancers, who whisper his name and giggle when he passes. Just as Shakira begins to rehearse, the artist born José Álvaro Osorio Balvín — who has, until now, never been to an American football game in his life — turns around and tightly hugs his longtime co-manager, Fabio Acosta.

To have a place at one of the most-watched TV events alongside the biggest names in Latin music is the kind of success Balvin has been after for some time. He says that while growing up in Medellín, “one day I realized that in Colombia, Shakira is the face of pop, Juanes is rock, Carlos Vives is vallenato” — a kind of traditional Colombian folk music — “but we’re missing the urban genre. From that moment, I decided to do this. I said, ‘Let’s take on the world.’ ”

And he did. In 2017, “Mi Gente” (which also features French singer-producer Willy William) became the first Spanish-language song to top Spotify’s Global 50 chart. It also rose to No. 3 on the Billboard Hot 100, thanks to a remix featuring Beyoncé. The following year, Balvin hit No. 1 with “I Like It,” his bilingual collaboration with Cardi B and Bad Bunny. Then, in 2019, he became the first Latin act to headline Coachella and was the second-most-viewed artist on YouTube in any language (behind Indian singer Alka Yagnik, whose music soundtracks many Bollywood films). He currently ties fellow Latin star Ozuna as the artist with the most videos in the billion-views club, with eight videos as both a lead or featured artist.

In achieving all of this, Balvin has helped reshape Latin popular music as urbano — the catch-all term for more rhythmic-leaning Latin music, predominantly reggaetón — has become its dominant force. Reggaetón, the mix of dancehall, hip-hop and Caribbean rhythms that came out of Puerto Rico in the mid-1990s, first hit the Billboard charts around 2004 but has become ubiquitous in the past few years thanks to artists like Balvin and Ozuna. In 2019, 23 out of the top 25 songs on Billboard’s year-end Hot Latin Songs chart were reggaetón or reggaetón-inspired, and eight of the top 10 Latin artists that year fell under the urbano umbrella. Balvin, who ranked at No. 3 on the list (behind Bad Bunny and Ozuna, respectively) is one of the de facto leaders of the movement.

But the halftime-show gig, which offers huge streaming, sales and tour boosts to even the most well-known stars, is still something of an introduction to mainstream U.S. audiences for Balvin, who despite his chart successes is not yet a household name — and not shy about wanting to become one. Last fall, after amicably parting ways with longtime manager Rebeca León, he joined Scooter Braun’s SB Projects, where he’s now managed by both Braun and Acosta.

With Braun’s help, he renegotiated his Universal Music Latino deal, which, sources tell Billboard, is worth hundreds of millions — commensurate with what a major pop star would get and one of the most lucrative contracts ever for a Latin act. As Balvin prepares to release his ambitious new album, Colores, in late March, he’ll also benefit from a new global priority program at Universal Music Group that’s available to only a handful of artists across the company and offers additional marketing and promotion resources to elevate their careers — just ask 2019 breakout star Billie Eilish, who took part in the program’s inaugural year.

Yet even as he takes his career to the next level, Balvin insists on doing it his way. Though fluent in English, he sings predominantly in Spanish and posts often on social media about spreading Latino pride and culture. He is open about his struggles with anxiety and depression at a time when the topic remains somewhat taboo in Latino communities. And with Colores — a concept album in which each song is named after a different color and will receive an extravagant, fashion-forward video to match — he’s aiming to prove that he’s not just a go-to collaborator on hit singles, but an auteur in his own right.

“One of my great dreams is to be a billionaire,” he tells me in Spanish. “Not because of the money — it’s not like you can fly two private jets at the same time if you have a billion dollars instead of 100 million. It’s about making a statement: Yes, we can. Carlos Slim is a billionaire in Mexico. Great. But we’re talking billionaires in the entertainment world — like JAY-Z, who has been an inspiration for me. Why isn’t there a Latino there?”

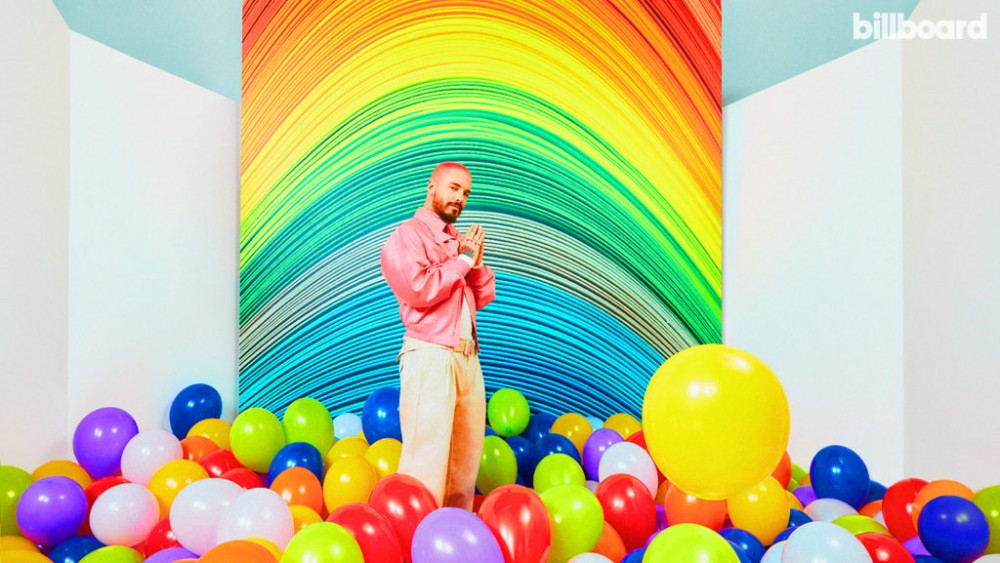

For a guy who makes lofty pronouncements about achieving billionaire status, Balvin is surprisingly low-key in person. When we meet again a week after the Super Bowl at a beachside Miami studio complex, he’s dressed simply in a T-shirt and jeans, his pink hair buzzed short. He doesn’t drink, doesn’t like to party and rarely goes out — you’re more likely to find him logging hours at the gym than the club. Balvin lived for a while in New York, where he relished being able to run out and get coffee in near anonymity. Even though he’s now living back in Medellín, he prefers to travel without security. (He does, however, have an assistant and his personal photographer with him today.) He often appears in photos with his hands folded in front of him, prayer-style, like he’s just happy to be there, and he eagerly shares goofy-looking throwback photos of himself — reading comic books as a tween, with an old girlfriend — as if to dispel any mystique. “I don’t really feel famous,” he says. “I’m always surrounded by my friends, my people. To them I’m not Balvin, I’m José.”

Early on, his career was a family affair. As a college student in Medellín — he studied communications and international business at Universidad EAFIT — Balvin played two or three shows a week at local high schools to build his fan base, while his father, Álvaro Osorio, a former economist and marketer, quit his job to manage Balvin full time. (Today, Osorio runs his own artist management firm, Gofar Entertainment.)

Balvin’s hustle eventually caught the attention of EMI Latin, which signed him in 2011 and was acquired by Universal Music Latino the following year. Still, Balvin didn’t break through outside of Colombia until he released the Farruko team-up “6 AM,” off Balvin’s 2013 album, La Familia. The pulsing track, with a party-all-night video Balvin describes as a “Latin The Hangover,” mixed Farruko’s grit with Balvin’s smoother, more melodic stylings — and became an instant radio smash, hitting No. 3 on Billboard’s Hot Latin Songs chart. By then, Balvin was managed by León, who was simultaneously leading AEG’s Latin division and using her connections to land Balvin opportunities, including an opening slot on Enrique Iglesias and Pitbull’s joint tour in 2014. León also brought Acosta, a young Colombian executive with a background in management and promotion, into the fold.

Balvin, however, was a savvy strategist in his own right. Five years ago, when he was feeling frustrated by what he saw as a lack of support from Universal Music Latino, he reached out to the label’s chairman and CEO, Jesús López. “He phoned me and said, ‘I want to see you because I don’t feel comfortable with the way things are going,’ ” recalls López. The CEO was in Mexico but offered to meet the next day when he was back in Miami. Instead, Balvin flew that same night to Mexico with Acosta and met López in his hotel at midnight. “We spoke about the problems he saw and what I saw,” says López. “He said, ‘I want to be a legend. I want to leave a mark.’ And that’s when it started.”

To this day, Balvin prefers the direct approach. When he launched his 2016 album, Energía, with the single “Ginza,” he went to Universal armed with numbers about the song’s traction in Mexico, which historically has not been a reggaetón-friendly market, and convinced the label to push the song there. He has also been proactive in securing deals in the fashion world, where he has served as the first Latino male face of Guess, among other partnerships. It was Balvin who approached Nike about collaborating, not the other way around. “Of course they weren’t going to call us,” says Balvin with a laugh. “Because they didn’t understand. Now they do. I called, I explained, I showed them numbers and facts.”

“I always say 50% of José’s success is José,” says Acosta. “He’s involved in every detail, and he will personally call the head of the label or the Spotify programmer.”

In 2015, Balvin was in Los Angeles attending the Special Olympics when he passed Braun and his star client Justin Bieber in a hallway. “He approached us just to say he was a big fan of Justin’s music and a big fan of my work as a manager,” recalls Braun. “I didn’t know who he was, but there was something about his personality and charisma that made me want to stay in touch. We exchanged numbers and became friends, with no agenda or expectations of working together.” When Bieber decided to do a Latin remix of his song “Sorry” later that year, Braun called Balvin.

It planted a seed. After Balvin and León parted ways last summer (the two remain close and, by all accounts, speak often), Balvin wanted to find someone who could further grow his career on a global level. “I wasn’t trying to get more management clients, but the opportunity to work with him, the respect I have, the friendship I have for him — we just decided to work it out,” says Braun. “I had a great moment where Ed Sheeran, a friend of mine, said to me, ‘You got J Balvin? He’s huge!’ He’s so massive all over. Many people don’t even realize how big he is.”

Braun adds that it was “vital” to keep Acosta onboard, given his experience and connections in the Latin world. “I don’t think my management is] about ‘better,’ but about ‘different,’ ” says Braun. “What relationships can I bring to the table that weren’t there before?”

After linking up with Balvin, Braun immediately closed two major deals. First, he helped renegotiate Balvin’s contract and secured Balvin’s place in the company’s global priority program. “It wasn’t a tough negotiation,” says Braun. “It was a ‘Let’s continue this business together and go stronger than ever’ conversation]. They did right by José, and we did right by them.” The second? He secured Balvin’s halftime-show appearance. For 75 seconds in early February, the biggest stage in the world belonged to Balvin.

In 2016, Balvin was in the studio with Pharrell Williams, working on their song “Safari,” when the superproducer gave Balvin some advice: “ ‘Try to do an album like Michael Jackson,’ ” recalls Balvin. “Ten tracks, all his biggest hits and most iconic videos in one place].” Neither Energía — the album that contained “Safari” — nor its follow-up, 2018’s guest-packed Vibras, were that lean, but Balvin is finally putting the idea into practice with Colores: Ten songs that will each get an accompanying music video directed by Colin Tilley (Kendrick Lamar, Nicki Minaj, DJ Khaled) and featuring psychedelic imagery from Japanese artist Takashi Murakami. “I love to collaborate, but albums are made to create concepts and worlds,” says Balvin. “I put all my energy into creating 10 songs and 10 videos.”

Helping him along the way is his Mexico-born, Texas-bred creative director, Oscar Botello, better known as MLKMAN (pronounced “milkman”). The two met at a Mexico City bar around 2014, and Balvin later recruited him to work on the pop art-inspired visuals for Energía. MLKMAN has since worked with Balvin to develop every aspect of his visual aesthetic, including the smiley logo that appears on his merchandise and has become his signature. Today, it’s common for artists of all levels to hire creative directors, but in Latin music, Balvin was an early innovator when it came to branding himself. “I feel that before Energía, artists in our world didn’t really have logos or emblems,” says MLKMAN. “That role didn’t really exist before.”

As ambitious and eye-popping as the visuals are though, Balvin notes that the actual music is not particularly edgy — it’s “easy to understand,” as he puts it, so it can reach as many people as possible. (A collaboration with Nigerian artist Mr Eazi also suggests a bid for greater international appeal.) When I point out that on the Colores track “Negra” it sounds like he’s talking about hitting someone during sex, he immediately corrects me and starts annotating his lyrics on the fly: “No, no! Not hitting! She wants mischief. She has a devil hidden inside. That’s sensuality. What woman doesn’t like a little palmadita when she’s intimate? That’s reality!”

Underneath all that color and sensuality, though, is something a little darker. About six months ago, Balvin started opening up onstage and on social media about his struggles with depression and anxiety. They began in his early 20s, when he started to experience debilitating panic attacks while on the road touring those high school shows. “I didn’t know what was happening to me,” he says. “I thought I was going crazy. A panic attack comes out of nowhere and you feel like you’re in imminent danger — your heart speeds up, you think your heart is going to burst.”

While the conversation about mental health in music is louder than ever, with both pop stars (Justin Bieber, Selena Gomez, Halsey) and rappers (Kanye West, J. Cole) talking about their experiences, it’s not so widely discussed in Latin music, especially in countries like Colombia. Balvin, who takes medication and meditates daily, hopes his openness will help reduce any remaining stigma.

“I want to erase that line that has been drawn in the entertainment world that paints artists as a perfect person with an absolutely fantastic life. It’s not like that,” he says. “There’s a human being behind the character, and he has feelings. He suffers, he has friends, he has enemies, he has problems. My great vision as an artist is to humanize. It’s saying, ‘I’m like you.’ ”

Things looked pretty perfect for Balvin at the Super Bowl — there he was, singing in the language of his choice, wearing clothes he helped design, shouting out his “Latino gang,” bouncing up and down as Lopez shook her booty against him. But even global megastars have to deal with nerves, says Balvin. So just before taking the stage, alone in his trailer, Balvin turned off the lights, put on his favorite reggaetón songs and some funky glasses, and danced till showtime — just as 12-year-old José would.

J Balvin will appear at the 2020 LatinFest+ by Billboard and Telemundo, held in Las Vegas April 20-23. For registration and ticket sales, go to latinfestplus.com.

This article originally appeared in the Feb. 29, 2020 issue of Billboard.