Lil Wayne’s notorious rock album “Rebirth” continues to stand out as an aberration in his discography, but is the divisive album simply misunderstood?

An artist cannot control their creative impulses. Nor should they. We’ve long seen comfort zones left behind in favor of newer, but not necessarily greener pastures.

It is, after all, part of the artist’s eternal curse. The fans want change almost as much as they inevitably come to long for the glory days. The “old” insert artist’s name here. In favorable situations, the change might elicit criticism at first, only to be damn near revered years later; consider Radiohead’s transition to Kid A, or ’s to 808s & Heartbreak. For those who aren’t so lucky, the detions are shoved into the closet to collect dust, aberrations better left forgotten. Alas, such was indeed the case for ’s foray into the mire that is rock-rap, his seventh studio album Rebirth. At least, at first glance. Ten years later, is it really as bad as the initial reviews would have you believe?

There’s a case to be made that Rebirth wouldn’t exist without “Lollipop,” . Despite having previously established himself as one of the game’s deadliest lyricists — by a wide margin at that — Weezy opted for simplicity in both bars and arrangement. The end result was a seductive club banger strangely appropriate for stadium play, a combination that helped “Lollipop” clinch the position of being the most popular song of Wayne’s career. It’s no wonder he was, at minimum, enticed at the prospect of further exploring this potentially lucrative road. And thus, Lil Wayne’s first “rock album” was born — a flight of fancy perhaps, but one well-earned. Even now, if there’s anything to be said about the project, it’s that there remains a clear sense of artistic freedom throughout.

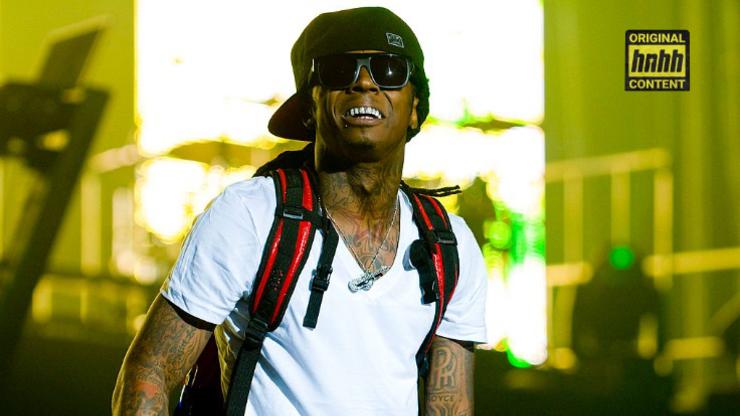

Tim Mosenfelder/Getty Images

Seeing as rock and roll music is a historic and expansive genre that has spawned countless subgenres, simply slapping a “rock” label onto an album does little in revealing a clear sonic direction. A rough translation might be better served as follows: there are guitars and loud drums. Guitars played by Weezy himself, if that’s worth anything on your scorecard. As such, he should be judged as a guitarist, from technique to tone. For the most part, Wayne tends to soak his chords in distortion, heavy on the sustain. Sometimes his riffs are shrill and piercing, closer in spirit to heavy metal than a typical rock band might employ. Other times they’re surprisingly whimsical, seeped in the fairy-tale romance of the pop-punk radio playbook.

Such is indeed the case on the -assisted “Knockout,” which feels directly plucked from a late-nineties summer camp comedy. The strange thing is, Weezy’s ear for melody is surprisingly solid; his vocals never lack sincerity, which in turn helps him swerve the pitfalls of parody. It’s clear he genuinely enjoys this style of music, having previously developed friendships with the likes of Pete Wentz, Green Day, and Gym Class Heroes. Unfortunately for Wayne, the direction was so left field that many of his longtime listeners were simply incapable of making the jump — to appreciate Rebirth not only required a stalwart dedication to the man behind it, but to the music he was attempting to explore. Otherwise, enjoyment for Rebirth was wholly dependent on one’s threshold to suffer through a genre they don’t even like out of sheer loyalty.

Tim Mosenfelder/Getty Images

At times, it seems as if Weezy was driven by caffeine, unchecked energy, and pent up sexual frustration, all but shrieking out his words on songs like the frantic “Price Is Wrong.” Lyrically, Weezy seems to have taken the schoolyard romance concept and run with it, pitting himself as the leading man in a John Hughes-esque adventure — albeit one slapped with an NC-17 rating. The pattern is arguably at its most obvious on the infamous “Prom Queen,” the lead single and first taste of Wayne’s vastly different energy. For many, the song became an easy target, if only because of how different it was. On the surface, there’s little on Rebirth that jumps out as being overtly hip-hop. But one look at the liner note credits might prove surprising. Production is handled by a laundry list of familiar names, with heavy involvement from Cool & Dre, J.U.S.T.I.C.E League, and Streetrunner. contributes a Recovery-era verse on “Drop The World,” a largely rapped duet picking up where “No Love” left off. Wayne does come through with a few bars here and there, but for the most part remains fully dedicated to the world of sex, drugs, and rock and roll.

Upon its release, critics and fans alike weren’t exactly kind to Rebirth. It quickly became the butt of many-a-joke, painted as a musical midlife crisis — one largely made up of underdeveloped songwriting from an underqualified source. But did those negative sentiments withstand the test of time, or did they melt away in favor of a newfound rosy-tinted perspective? In hindsight, many songs on the album seem to have garnered appreciation, if not exactly acclaim — especially given the clear influence Rebirth had on many of the new generation’s younger artists. Especially the likes of Juice WRLD, XXXTentacion, and Trippie Redd, all of whom included elements of rock and metal in their own catalogs, though never quite with Weezy’s headlong dedication.

Even if it wasn’t the music itself that proved particularly inspiring, the willingness to boldly attempt a complete reinvention in the name of fun is undeniably admirable. As such, it further solidified Lil Wayne as a fearless artist, willing to follow a creative impulse straight off the cliff, provided that’s where it took him. It may not be your cup of tea, but there’s an argument to be made that Rebirth deserves respect, not ridicule. So many rappers fancy likening themselves to rockstars, but few are willing to commit to the cause so thoroughly.