In 2010, Wolfgang Gartner was eight years sober from drugs and alcohol. That is, until, the night before his first-ever Coachella performance in April of that year — when he saw a full, open beer at a party.

“Without even thinking I just grabbed it and started going,” he says. “It wasn’t even a choice I made.”

By the next night, he was doing drugs just prior to going onstage, self-medicating to deal with the performance anxiety that had been an issue for much of his career. The Coachella show was a smash, serving as one of the launchpads that placed the producer born Joey Youngman at the forefront of a dynamic dance music scene — one that was on the verge of blowing up in the U.S. and beyond at the turn of the decade.

“I don’t want to say that drugs were good for my performance in any way,” Youngman tells Billboard Dance via Zoom from his house in Los Angeles, “because that’s a really bad message to send, but I was able to play very well at all times under the influence of pretty much anything, and that’s been the case throughout my entire life.”

Like many people in the dance scene, for Youngman drugs were always part of the equation. As an up-and-coming producer in his native San Luis Obispo, CA, ecstasy was the substance of choice for him and his peers. He first went to rehab in 2000 at age 20 to deal with his reliance on this drug, successfully staying sober until April of 2010.

Challenges relating to anxiety, depression and substance abuse didn’t top his ascent. In the decade since that debut Coachella performance, Youngman experienced some of the highest peaks that the global dance scene has to offer, playing many of the world’s biggest dance festivals including Electric Daisy Carnival, Ultra, Electric Forest and Creamfields and returning to Coachella in 2013. He toured the world, delivered an excellent 2010 Essential Mix and released a pair of albums — 2011’s Weekend In America and 2016’s 10 Ways to Steal Home Plate — that captured a massive and powerful sonic style amalgamating electro, funk, house and bass and which placed him alongside genre contemporaries like Skrillex, deadmau5 and other scene stars.

While Youngman has consistently released music for the last ten years — with a flurry of singles coming via major dance labels including Armada, Spinnin, Ministry of Sound and his own Kindergarten imprint — by the summer of 2019, addiction had significantly diminished Youngman’s creative spark. Instead of focusing on music, his days became largely dedicated to drug use. [Youngman declines to name the specific drug he was using on record.] Realizing he had an issue he couldn’t solve on his own, he checked himself into a rehab facility in Tucson, AZ in August of 2019.

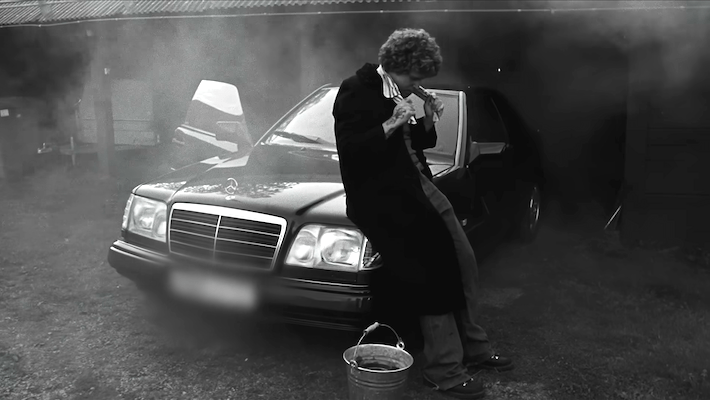

His latest body of work, Tucson, is named for that experience. Out today (June 26), the EP’s lead single “Supercars” is a futuristic, disco-inflected house thumper, with the excellent six-track EP (out July 17 via ALT:Vision Records) populated with music made both before and after his 30 days in Tucson and another month at an outpatient facility in Los Angeles. This project is the beginning of a barrage of new music Youngman has on deck, and he says he’s “wayyyyyy” excited about the solo work and collaborations that are on the way.

Here, Youngman, now 38, discusses his decade in the dance scene, the circumstances that led him to Tucson and why he’s “incredibly optimistic” about the future.

Was drug use always linked to anxiety for you?

Yeah. In rehab they call it dual diagnosis, which means that you’re abusing substances because of some underlying psychological reason or diagnosis, which is usually depression or anxiety or whatever else. That’s true for a lot of addicts and alcoholics. That has been my thing throughout both of my stints in rehab; I was really compensating for underlying anxiety and other mood issues, just trying to make myself happy and comfortable in social situations. That’s a large reason I did drugs my entire life.

For someone with social anxiety to be in a profession where half of the time you’re alone in the studio and then half of the time there are 10,000 people standing in front of you — what was that like?

It was around the time of that first Coachella performance that my anxiety was so bad that I went to my psychiatrist — I was already seeing a psychiatrist for depression – and was like, “I need you to prescribe me something so I can handle this shit, because I can’t handle it anymore.” And they did, and I became addicted to it and had to be taken off of it in rehab.

As your career got bigger, did your addiction also expand?

I think it did go hand in hand. I think the larger the audiences got, the more pressure I was under. The more pressure I was under, the more anxiety I had, and at [that] point I was self-medicating my anxiety.

You’ve had a lot of really incredible career peaks. Were those moments purely enjoyable, or was it always walking the line between your success and the challenges of addiction?

For me the shows — those big shows — were incredibly fulfilling and enjoyable, but mostly from the minute the set ended. [It was] the satisfaction of having played it, and the memory of playing it. But during that hour and ninety minutes, it was so much pressure. Because when you’re playing for five or ten or 20,000 people, you cannot f–k up. You cannot f–k up one time. Unless you’re playing an Ableton set and it’s all pre-made and s–t and there’s no trouble — but I’m actually mixing music and doing real s–t, and I could f–k up.

So the entire time I’m up there, it’s a rush and it feels good. But the real reward comes when you step off the stage and you realize what just happened, and you look out at the crowd like, “F–k yeah, that was one of my milestones in life.”

When did it start to affect your passion and enthusiasm for music, and your ability to make it?

This most recent addiction really just killed my drive, my passion. The drug became the only thing that I thought about. And it was no longer about doing drugs to make better music, it was literally just about doing drugs, period. So throughout all of my prior addictions in life, drugs and music kind of went hand in hand, and I used the drugs to boost my creativity, I thought — or tricked myself into thinking it was better for me. With this past year, with what I got into, there was no desire to do anything but do drugs.

How did you know it was time go to rehab? Was it your decision, or were you encouraged to go?

It was totally my decision. My wife at the time, we’ve separated now, had no idea [I was on drugs]. My parents had no idea. I think my managers knew. They did know. My manager has been through this s–t with me before, and he knows you can take a horse to water, but you can’t make it drink. I have to come to that decision on my own.

There was no one thing that happened that made me check into rehab… Everything just kind of fell apart in my life, and there was a moment when I realized I was going to have to get help. I had started seeing a therapist with the sole reason of trying to get off drugs via therapy, which is… I even knew that was an insane thing to try and do, but I was trying to do it low-key and undercover without going to rehab, so nobody found out what I had been doing. I was trying to make it so nobody knew it had ever happened. It did not work.

On a creative and spiritual level, what was rehab like?

Super-humbling. It’s an expensive rehab. The list of famous actors that have been through there is inane. You share a room with somebody. It’s a small room, and there’s two beds in there. I have a roommate, this big dude from Alabama with anger issues, and I’m sleeping in the same room with this guy, and they wake you up at 6 a.m., and you have to get up and out of bed. That’s how rehabs generally go. So it’s humbling — and you also have to obey authority, which isn’t something I’m used to doing.

When I’m paying for it myself, I want to get my money’s worth out of that s-t. That’s a big part of it. Spending that much money to get sober is half the reason you actually end up staying sober. Because it’s like, I spent $40,000 on rehab, if I relapse now it’s all down the drain. It helps me stay sober, honestly. [Laughs.]

When did you feel your creativity and your passion for music come back?

Here’s what I think it was: Making music, for me, is like exercise. And when I haven’t done it in a long time or if I’m not doing it very often, I can see retrospectively that the quality of music that I’m making is not very good. And when I’m just cranking them out nonstop, the music is actually better. For me, it comes down to creativity being a muscle, and I have to exercise it. That’s why it took so long after rehab to get it back. Getting on that treadmill then walking a mile, then two miles, then three miles, then walking with the f–king dumbbells.

Once my muscles started getting bigger, I started actually enjoying the exercise more. It’s a perfect comparison for me. So for me it was a matter of redeveloping my creative muscle and stylistically sort of – it’s almost like I had a musical identity crisis too, and I didn’t know what I was going to do, and if I was going to keep working in the box that I had built for myself or make a sharp turn and start making real house music again. I still haven’t decided, and I don’t think I need to.

Was there ever a moment where you considered giving music up completely?

Oh yeah. Totally. When I was in rehab, I was seriously thinking about it. For some reason, when I was there I came to the conclusion that music was a large part of the reason that I did drugs. A lot of the reason that I did drugs — because I thought it boosted my creativity, because it made work more enjoyable, because it made me happier, because it reduced anxiety — I thought that music was part of the reason I was doing drugs. So I thought if I wanted to live the rest of my life and stay clean and healthy, I’d have to get out of this industry and probably have to do something focus on recovery or helping other people who hare having trouble in their lives.

I thought about being a therapist, because I’ve had a of of therapists in and outside of rehab that have helped me a lot in my life. I like therapy. Or maybe be a drug counselor at a rehab. Obviously none of these jobs were large paychecks or anything, but I was kind of in the mindset of just needing to get out. I was even thinking that for a month or two after I got out of treatment. I was still kind of on the fence about everything.

And then what happened?

My dad and I always talk about music and my career and everything. He played in bands in LA in the ’70s and was trying to make it big and get a record deal, so there’s a connection there. About ten years ago we had a conversation and he asked me, “Are you an artist, or a businessman?” I said, “Well, I’m both.” He asked again, and I said, “I’m both — because I’m an artist and I have a business to run, which is my art.”

I never forgot him asking me that question, because it seemed profound. And earlier this year I thought of him asking that and called him and said, “Dad, do you remember asking me this question ten years ago?” And he said “Yes, I do’ and I said, “Did you intent it to be as profound as I think it is?” He said, “Yes, I did.”

And I said, “Well, I realize the answer is that I’m an artist, and that’s it. I’m not a businessman. That’s who I am. I’m only an artist, and that’s the only thing I will ever be.” That’s what came out of everything, realizing that making music is who I am, and I’m always going to have to do it, and I kind of suck at the business side of it. Every time I try to think like a business man when I’m in the studio, it doesn’t come out that great. So above everything else, I’m an artist.

Obviously it’s a challenging time for anybody to release music, so why is this the right time for the EP, and what does success for it look like to you?

Well, the right time to release the EP was January when it was originally supposed to come out. So now it’s the right time because it exists and I need to get it the fuck out there.

Are you excited?

Oh yeah. It needs to come out. That’s the thing, it’s so frustrating because I’ve been sitting on some of that music for two years… So it’s going to be a huge sigh of relief when it’s out there, just to have music out there for people to know that yeah, I’m still doing it, and that I have been doing it this whole time basically. I didn’t go away. I mean, I did for a short period of time, but I’m still doing it. I’m way more excited about other things I’ve been working on since that EP. I’m very happy about it, but the things I’ve started since then and a few collabs I’m doing, I’m way excited about, and I’m extremely optimistic about the future right now.

So it’s fair to say that’s there’s more new music coming from you.

Oh yeah, way more. I make little ideas and demos now and sit around with all of them and see which ones I want to develop and which ones I want to turn into collaborations and who those collaborations might be with. I’m approaching it from a new direction right now. Also I realized that if I’m ever going to get back to a good place in my career, it’s going to be with the help of other people. I’m not going to be able to do it on my own, so I’m actively working with a number of other artists right now.

Also what’s happening with COVID right now, I’m getting the vibe from these people that we’re all trying to lift each other up right now, because we all need help. None of us are playing gigs. We all need more income from music. So I feel like we’re all like, “Hey, let’s some money guys! Let’s do some shit and try not to lose our homes.’

What do you want to say to other artists dealing with the same type of issues you’ve been dealing with?

There are many songs that I have written in my career and in my life that I consider to be my best songs, and I wrote those songs completely sober. That’s what I always remind myself. Although some of my big songs were written under the influence, many of them were not. And I remember which ones were not, and some of them are incredibly good. My best work. I’m thinking “Illmerica,” “Space Junk” — those two I made when I was stone cold sober, and I remind myself of those songs because those are two of my favorite songs I’ve ever made.

If you hit a point when you feel like you had to use drugs to make music, it’s probably time to get help. Once you’re on the other side of that help, and you get better, it might take some time, but you can absolutely nail it sober, whether or not you think you can right now, you can. And I’m speaking to myself in the past, from the future.