Just moments into Willie Nelson's Tuesday (Jan. 14) concert at squeaky-clean Toyota Arena amidst the office parks of Ontario, California, a thought fluttered in and hovered nearby for the next entirely pleasant hour. If you can't get casual with Willie, who the hell are you gonna get casual with?

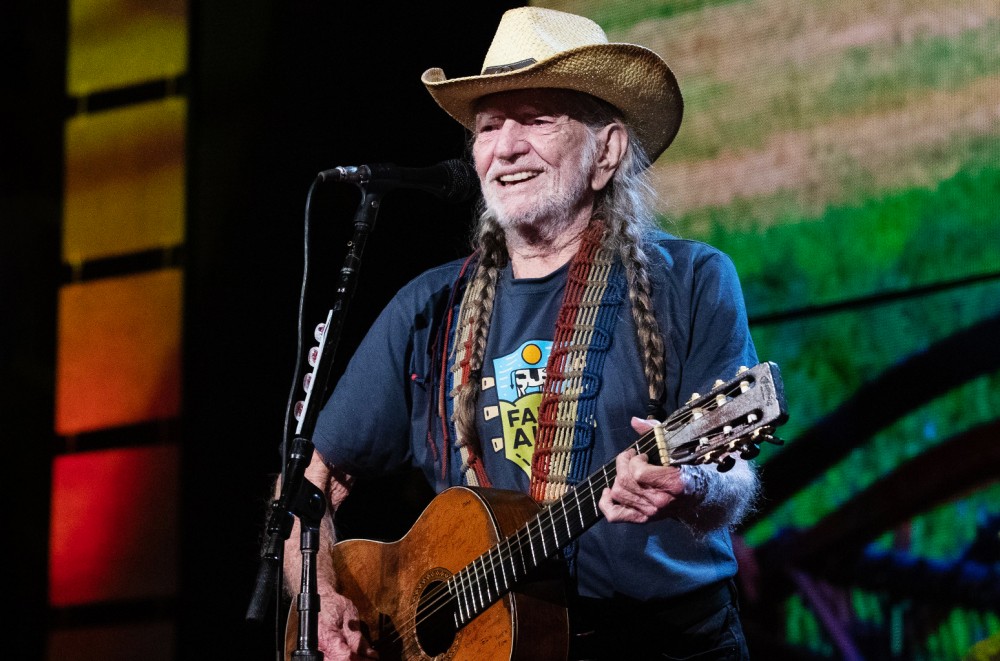

The crowd surged to their feet the instant he stepped into the spotlight, raising his arms less like a monarch and more like a regular gent plucked from a crowd to speak his piece. At 86, spindly under a black t-shirt that bears the name of a favored village (Paia) in Hawaii, he's craggy of feature, with a hawk's hooded, alert eyes. Without a word, he and his family-centric band launched into that half-mournful tale of dissolution, "Whiskey River." Over time, the dire lyrical messaging has yielded to the infectious beat and croon-able chorus to become an anthem.

At one level the song stands in for all the hard road he's seen — early struggles to be heard, relationships collapsing, a famous hassle with the IRS, and in recent months an onset of lung conditions that postponed this very tour. His fame, our sense of his contrarian yet warm essence, sprawls across generations. We've lived with that song since Willie first put it out in 1973 on Shotgun Willie. A paean to lost love with its refrain "Don't let her mem'ry torture me," it's also an ode to a kind of capitulation that hardly matches current trends in wellness-obsessed America: "Whiskey River don't run dry/You're all I've got take care of me." The song's co-author Johnny Bush and Willie would become honky-tonking buddies and record together, but the song has become Willie's, despite the fact that he long ago, and ever so legendarily, gave up alcohol for the comforts and inspirations of pot.

Many Willie classics now have a comfortable aura of pop culture meta surrounding them — bulletproof crowd-pleasers that must be heard because they wafted out of car radios to form landmarks in our lives. Certainly the evening would include his "On the Road Again" (though skipping his unforgettable ballads "Crazy," "Blue Eyes Crying in the Rain" and "Angel Flying too Close To the Ground") and an array of loosey-goosey tunes sequenced nicely with such indelible covers as "Always On my Mind" and "Mammas Don't Let Your Babies Grow Up to Be Cowboys."

Part of the meta is a storied defiance of convention. The Willie we associate with boozing songs could be, in the words of his great outlaw brother Waylon Jennings, lonesome, ornery and mean — or at least, as one old friend has put it, "a little sarcastic." But when a fellow songwriter from the fringes of a Nashville system both loathed proffered a first joint, Willie was abruptly en route to an entirely re-stocked bad boy rep. Lately he's monetizing the weed legend neck and neck with Snoop (they've gleefully met) as our most baked showbiz figure.

Another part of it is grander, but just as hard to pin down. Beto supporter though he became, Willie also partakes of a certain good ol' boy streak epitomized by country giants Merle Haggard and Jennings (he long lived with the same anger Waylon belted out in "Are You Sure Hank Done It This Way"). The kind of Willie fans who fell in love with the conceptual masterwork Red Headed Stranger were comfortable enough with the mythically violent underbelly of the title character ("He's wild in his sorrow"). They might, however, harbor doubts about the second song in his set that night, Toby Keith's "Beer for My Horses": "We'll raise up our glasses against evil forces singing/Whiskey for my men, beer for my horses…." Finishing that couplet, Willie in a familiar gesture raised a finger in the air to the crowd's roar. Whatever has fueled America's political polarity — and even his red-hatted constituency knows he's long leaned thoroughly left — the law-and-order lyric from the politically elusive Toby Keith clearly scratches some indefinable itch.

There's no easy description for the audience — plenty of camo gimme caps (though a quick walkabout yielded almost no strictly political signifiers), plenty of sturdy white dudes in boots and cowboy hats, and many regular citizens just slugging tall boys and singing along at multiple points ("Roll Me Up and Smoke Me When I Die," anyone?). This 11,000-seater stands on the ground where the Ontario Motor Speedway once hosted a landmark Evel Knievel stunt and is just as much part of Los Angeles' urban sprawl as it is the gateway to (and biggest nearby venue for) what's called the Inland Empire.

The Tuesday night concert was the finale of a tour leg that had been postponed when Willie had to temporarily beg off last August due to lung conditions robbing his breath. If he talked a few of the windier lines that he once might have sung, he still displayed a strong, confidently note-nailing voice. And he was, as usual, bewitchingly fluent on the famously battered acoustic known as Trigger, steadily displaying his committed, string-bending picking.

But what made the night feel like a declaration of the master's right to be adventurously flexible was the show's devotion to that family side.

Ever since Neil Young scooped up elder son Lukas Nelson and his band Promise of the Real, Lukas' wide-ranging talents have been nicely showcased, as in the useful authenticity he brought to A Star Is Born both behind the scenes and onscreen.

When he stepped forward to do the '50s blues song "Texas Flood," taking his time to delve into it with a stinging guitar solo much as his early role model Stevie Ray Vaughan had done, he had the crowd's full attention. Similarly gifted on electric and acoustic guitars and a variety of percussion chores, younger brother Micah was introduced by his slyly grinning dad to do "One of my favorite gospel songs." This turned out to be a winningly wackadoodle screed entitled "Everything Is Bullshit," in part a face-slap aimed at mobile electronics: "Make a profile for your Snapchat/Murder people from a distance…"

The crowd seemed to find that hot mess of a tune pretty damn outlaw. Certain immortal figures inevitably got some love with Jennings' "Good-Hearted Woman," Haggard's on-brand collab with Willie "It's All Going To Pot," and a Hank Williams sampling. The show headed for home with the goofy Mac Davis song "It's Hard To Be Humble" and Johnny Paycheck's "I'm the Only Hell (Mama Ever Raised)." The net effect of the entire evening was to chase away whatever grim forebodings are contained in Willie's recent set of albums — billed as "The Mortality Trilogy" — in favor of a much more frolicsome mood. Having slung his own cowboy hat into the crowd, the braided, bandanna-sporting Willie all but skipped through "Will the Circle Be Unbroken" and seemed glad to leave us laughing. If his tenderest vocal of the night had come with a feelingly repeated phrase from "Always On My Mind" — "I'll keep you satisfied" — he had done just that for the assemblage.

And just about the first thing on wheels to leave the parking lot as the building emptied was Willie's gleaming gargantuan bus, on the road yet again.