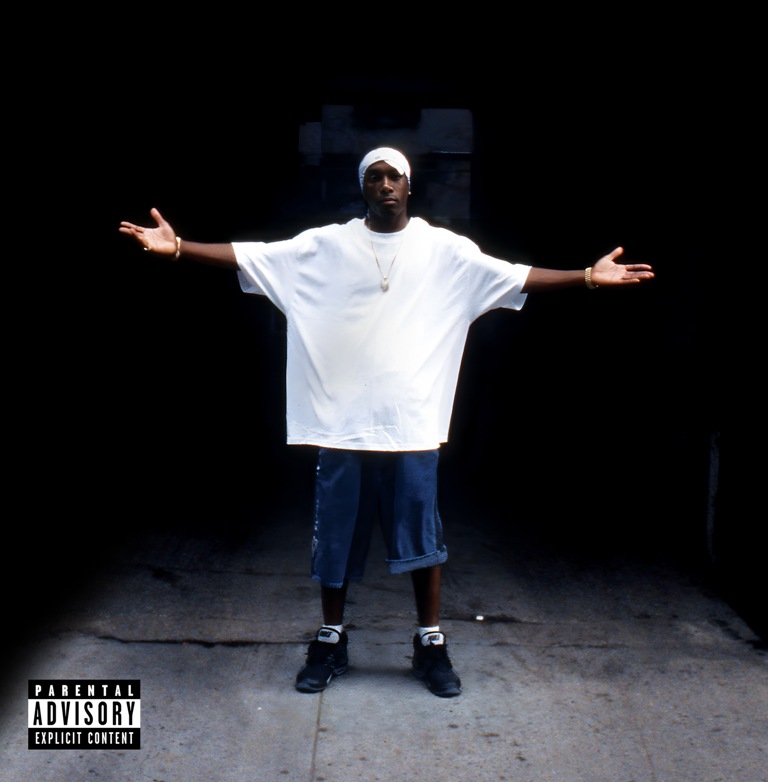

Photo Credit: @dreadlotus

Eritrean born, Camden raised wordsmith Awate is undoubtedly one of our most on-point, principled artists. Thematically, he’s a don at connecting the dots, from the struggle for Black life at the grassroots, to the structural racism which necessitates the struggle in the first place, to global struggles against racism, injustice and inequality.

But don’t get it twisted, Awate is no inaccessible, encyclopaedia rapper. His flow, musicality and knack for vivid storytelling speak directly to the people he seeks to uplift. Coupled with the competitiveness and confidence required to flourish in the rap game, Awate offers listeners food for thought and undeniable, volume-up vibes in equal measure.

Black Lives Matter Always, but with George Floyd’s murder by police in Minnesota, the fight has re-entered the wider consciousness. Here in the UK, Black communities are leading us into what is hopefully a reckoning with our own wickedness.

Against this backdrop, Awate blessing us with All Good Things, a surprise EP consisting of loosies and Happiness remixes from long time collaborator Turkish Dcypha, feels especially poignant. Turkish’s soulful soundscapes, coupled with smart features and re-imagined verses, breathe new life into familiar territory and are a timely reminder of Awate’s significance to the scene.

Project opener, Austerity sets the tone for these turbulent times perfectly –

>

“One of my favourite hobbies is to find and beat swine

I can’t help it. They’ve killed too many people of my colour and my class for me to sit and be quiet.”

With all due to respect to D.Tail and Britizen Kane, Awate absolutely spins them on the Fresh Product remix with an uncompromising, braggadocios new verse.

For me, The Brutalism remix is the Ep’s standout. Turkish Dcypha’s mournful production remains as affecting as ever. The addition of verses from Krucial, Big Ben and A Star, along with new bars from Awate himself give the track layers upon layers of depth as each artist interrogates the complexities of road life –

>

“Where I’m from the streets are cold, froze from the temperature

Youth centre closed, old foes send for ya.”

The project closes with An Intermission To The Struggle For Black Life. As a non-Black person writing this, I don’t feel like my words can add anything to the weight of Awate’s here. For any non-Black person reading this, next time, be there.

>

“On the streets

All of us, all of us on the streets

Next time they take our brother, next time they rape our sister

Next time the press paint a picture of this not being a racial issue

Next time I can’t get a job or can’t get a flat or school holds me back

I’m not having it”

Robert: All Good Things is a collection of loosies and reimaginings from Happiness. Why were you keen on exploring those records again, while you’ve got an LP cooking?

Awate: I don’t know what it is, but I really enjoy going back over things and thinking about them from different perspectives. When my cousins and I would watch films, I was always rewinding a joke again and again until I understood how it worked and my cousins hated me!

The Fresh Product Remix was a surprise, Turkish sent me an email of my song with D.Tail and Britizen Kane going HAM on it and I was partly offended! That kind of competition is amazing and it was fun to let them know what I thought of their verses and then also see their reactions when I added my verse to it.

I think the idea for the project came from The Stone Roses who had a compilation project called The Complete Stone Roses which had the b-sides to the singles from their first album and a bunch of reworked backwards tracks.

If you had to boil down your musical influences to a few key figures, who would they be?

So, I’ve done this list a lot and it’s mostly the same rotating list of fifty artists. Really quickly, I’ll go for Ms. Dynamite, 50 Cent, Fela Kuti, Yasiin Bey, no name, The Stone Roses.

But there are a lot of artists and works that I’ve really learned a lot from. One song I’ve been thinking about recently is The Parasite by Eugene McDaniels which is really, really powerful, witty, smart, subversive and funky. I swear it’s so beautiful and uncomfortable to hear how he breaks down settler colonialism and genocide. Reminds me of ‘We Almost Lost Detroit’ by Gill-Scott Heron but it takes a different approach.

Do you think that drive to really understand how things work has helped shape your world view?

Oh, definitely. And it’s a constant process. My earliest quality was obsessive inquisitiveness, due to knowing I wasn’t born here and the way my mum raised me.

That perspective of being aware that you’re in this country because of colonialism makes you ask what colonialism is, how it functions, who else it oppresses and what struggles have been fought against it.

As a musician, it’s a real gift to keep asking why until you get to the actual root, elemental reason for an incident or the way you feel. It allows you to say a line, then interrogate that thought from different angles. Psychodynamic psychotherapy helped me with that a whole lot.

Revolution is in the air at the moment. As an artist who centers Black liberation in your work, how does it feel to drop music so relevant to the struggle, at what could be such a defining time?

We must strike a balance between openly and privately supporting these struggles and promoting and centering ourselves in the narrative. That’s quite complicated.

I’m not a capitalist. I am an independent solo artist, though, and my artist name is my real name so promo for my music is also raising my profile as an individual. Trying to draw attention to myself as some kind of leader, oracle or whatever is counter to what I believe in.

At the same time, I come from a family of revolutionaries and am aware that the Eritrean Liberation Front (and similar groups around the world) had a cultural troupe that would visit recently massacred areas to play music or distribute cassette tapes. These acts of solidarity remind people that they are not alone, that ideas of freedom are spreading and allow the artists a form of catharsis.

My favourite musicians, authors, comedians have condensed political theory into smaller and much more visceral fragments. Doing that is different to dropping music that does nothing to address the struggles or triumphs of the oppressed and push capitalist narratives of reform or charity like Drake’s ‘God’s Plan’ song and video.

You don’t just talk about the struggle, you very much be about it with your actions. Along with the responsibilities we all must take in fighting injustice and racism, do you feel specific responsibilities as an artist?

It’s fantastic but surreal seeing things that have been developing in the fringes for decades being discussed in the open. Prison and police abolition which have been championed by the likes of Angela Davis and Grace Ruth Wilson are now in the public lexicon.

We have to use our platforms to direct people to these ideas whether they’re books, articles, videos, podcasts, conferences etc. Once we have an understanding of the structures that oppress and discriminate, we can join forces with those doing the work to heal the world and develop new ways of dismantling division and inequality.

Tell me about your relationship with Turkish Dcypha. Does he bring the best out of you?

Yeah, for sure. Since we met in 2011, he’s been my main partner in music. Producing, mixing and mastering our records but also giving me support and advice.

He’s been in the game in several different roles for more than 20 years and I was a huge fan of Sway and what they were doing, being a kid who grew up in north London.

He gets what each artist he works with needs and gives them a bespoke sound. For ‘Happiness’, we stayed in the musical timeframe of 1968-73 which also informed the politics of the album.

Camden features heavily as a point of reference in your work. How did coming up in your ends shape you, and impact the music you create?

In my music, Camden is representative of certain characters, ideals and events. I’m from the borough in the middle of London known for being the cultural and bohemian hub. Where counter-cultures and genres of music are formed and cultivated. Where famous actors, musicians and Dukes live.

But for me, Camden is our network of infamous sink estates. The most neglected and ‘dangerous’ housing complexes that have been intentionally left to decay because people don’t see or care about us. The idea of Camden as a psychedelic bohemia comes from the mental illness, drugs and art in the area and the community attempting to tell people that.

When I write, I can’t help but reflect the people who are stuck in their sub-cultures, walking around as Punks, Mods, New Romantics etc. Camden is where history is most obviously living and breathing.

You recorded some of your upcoming, second LP in Brazil. What impact did your time there have on you, creatively and personally?

When I arrived in Sao Paulo, it was before Bolsonaro had been inaugurated but two months after the election, so people were still mourning the loss of the election but also gearing up for the resistance work that needed to be done.

It was actually Black Consciousness Week when I arrived. My itinerary allowed me to see hundreds of shows, exhibitions, street festivals and political events in just a few days! It was overwhelming to see the unity, revolutionary discourse and cultural aspect to their organising.

There were exhibitions on Black Women Martyrs and I saw murals of assassinated politician Marielle Franco everywhere, along with South African, Palestinian, Black American and LGBTQIA revolutionaries.

In the peripheral slums, the work being done to keep people safe really impacted me. From holding renowned anarchist graffiti festivals to raise money for flood barriers in Campo Limpo to building music facilities with no government or NGO support in order to combat the War on Drugs in Capo Redondo.

We have so much to learn from our brothers and sisters fighting the same battles around the world.