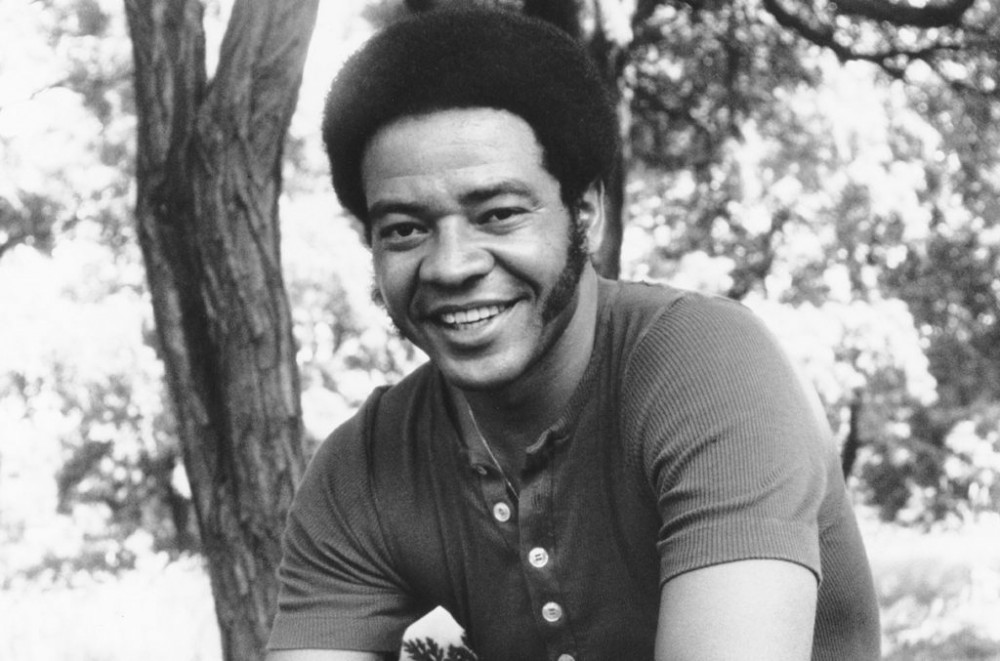

Bill Withers was a singular voice in the history of soul music — masterful and mighty, but modest and unassuming. Still Bill was the title of his most successful album, and also something of a guiding principle: Even on his biggest hits, you never got much more or less than the man himself, singing to you in a way that made you feel like he was just making conversation, even as he was making your heart leap or twisting your insides around.

The R&B legend died this week of heart complications at 81, leaving behind a legacy of classic albums, radio staples, and an entire second generation of further hits covering or sampled from his peerless singles. And of course, despite his all-time resume, he stayed humble to the end. “Bottom line is — check this out — Stevie Wonder knows my name,” he summarized in awe to close his 2015 Rock and Roll Hall of Fame induction speech, “and the brother just put me in the Hall of Fame.”

Here are our picks for Bill Withers’ 15 all-time greatest songs.

“Harlem” (Just As I Am, 1971)

The first track on Bill Withers’ first album comes out swinging, with a slow-build acoustic shuffle that builds into a string-laden, frenzied stomp by song’s end. Withers doesn’t hold back either, detailing the best and worst the titular New York neighborhood has to offer — including brutal summers (“Too hot to sleep, too hot to eat/ I don’t care if I die or not!”) and bad politics (“Our crooked delegation/ Wants a donation”), but also some pretty happening Saturday nights (“You can really swing and shake your pretty thing”). — ANDREW UNTERBERGER

“Ain’t No Sunshine” (Just As I Am, 1971)

Like Withers himself, his debut single, 1971’s “Ain’t No Sunshine” was a gentle masterpiece that quietly pioneered a new breed of R&B, melding sparse blues-folk rhythms with lush, soulful strings. It’s so gorgeously melancholy in its low-key wistfulness that you almost don’t realize he’s repeating the words “I know” over and over until he’s d–n near close to the 26th time. – JOE LYNCH

“Grandma’s Hands” (Just As I Am, 1971)

In a scant two minutes of acoustic blues reverie, Withers paints a detailed, nuanced portrait of a woman’s entire life – the quiet hardships, the tough benevolence – and how it fit into her community without ever describing anything other than her hands. A master course in poetic brevity. — J. Lynch

“Hope She’ll Be Happier” (Just As I Am, 1971)

One of the most devastating songs ever, made all the more vulnerable because of Withers’ conviction. Over guitar and organ (played by Booker T. Jones), Withers sings with a stretched-thin voice about how his girl no longer wants to see him. “I never thought that she really would leave me/But she’s gone” — as concise a summary of post-relationship shock as anything in the English language. Still, like the title says, he hopes she’ll be happier with her new guy. Withers was a master of repetition, of finding the perfect phrase and not letting you forget it, and this song contains one of his toughest: “Maybe the lateness of the hour/Makes me seem bluer than I am.” Nope. This is as blue as it gets. — ROSS SCARANO

“Lean on Me” (Still Bill, 1972)

Like the earlier decade’s “Let It Be” or “Bridge Over Troubled Water,” Withers’ signature ballad has taken on such near-hymnal significance and transcendence over the decades that it’s almost impossible to imagine it ever being a contemporary pop song. But of course it was — and an exceedingly popular one at that becoming his first (and, improbably, his only) No. 1 on both the Billboard Hot 100 and Billboard‘s R&B Songs listing in 1972. While its gentle up-and-down melody and message of unconditional support are unsurprisingly timeless — to the point where a much more playful Club Nouveau cover also topped the Hot 100 a decade and a half later — the main selling point is still Withers’ delivery, sturdy but not overpowering, helpful but not pushy. — A.U.

“Use Me” (Still Bill, 1972)

“Use Me” came one spot away on both the Hot 100 and R&B Songs chart to matching the supremacy of “Lean On,” and it’s not hard to see why the song was as massive as it was — or why it was just the tiniest bit less universally accessible than “Lean.” The belching bass-and-organ saunter is irresistible, but the subject matter — about Withers’ shrugging, even smiling acceptance of an emotionally abusive but sexually fulfilling relationship — was a little real for 1972 pop radio, and the song’s greatest joys come in its negative spaces, particularly the gleefully tortuous pause in between “You just keep on using me… until you use me up.” — A.U.

“Who Is He (And What Is He to You)?” (Still Bill, 1972)

Arguably the slinkiest groove in a career full of ’em, “Who Is He (And What Is He to You)” is an absolute master class in single-measure funk, one unsettling four-note guitar-and-bass loop that burrows its way further into your bones with each repetition. Withers matches it with a vocal that derives an entire universe of suspicion and betrayal from one passing glance from a stranger on the street — “I don’t know who he is, but I think that you do” — letting us draw our own conclusions about whether he’s really that intuitive, or just a jealous guy with his own s–t to work through. Either way, the word “dadgummit” never hurt so bad. — A.U.

“Kissing My Love” (Still Bill, 1972)

Withers kicks out the jams on this gloriously straightforward expression of lip-locked joy: “When I’m kissing my love/ I close my eyes and see a pretty city with a million flowers.” He sings about the blood pumping through his veins, and you can actually hear it in the bubbling bass, the wah-wah’ed guitars, the shoulder-shrugging drums. But best of all is when he stops singing altogether, just whistles his way to the song’s conclusion, floating away on the groove like in an MGM musical. — A.U.

“Let Me in Your Life” (Still Bill, 1972)

There’s bent-low and humbled, and then there’s Bill Withers on “Let Me in Your Life,” begging gently for love. The string arrangement cries while Withers makes his case: “If he’s the cause of your sorrow/Be glad that he’s gone away….please don’t push me away.” By the time you get to his quiet “la-la-la-la-la”s, you’ll be desperately trying to open your door to Withers, that all-time conjurer of our nakedest emotions. — R.S.

“I Can’t Write Left-Handed” (Live at Carnegie Hall, 1973)

For two minutes, Bill Withers speaks to the audience at Carnegie Hall in his mellow, lacquered voice about the Vietnam war while his band vamps and hums. He recounts being a young man, oblivious to politics and global conflict, and then he describes meeting an injured vet — his right arm had been amputated. Suddenly Wither starts to sing: “I can’t write left-handed/Would you please write a letter to my mother?” Booker T. called Withers “the poet Stax never had,” and it’s because of songs like this. — R.S.

“You” (+’Justments, 1974)

“You want to take me to a doctor/ To talk to me about my mind.” As far as album openers go, this one holds nothing back. A divorce album, +’Justments starts out scorching, with Withers excoriating for five solid minutes, no chorus. “You got the nerve to call me narrow-minded/‘Cause I’m not loose and indiscreet” is another representative couplet, delivered over nervous strings and funky piano and guitar. Withers could write vulnerable straight-talk, but his capacity for indignation was just as formidable. — R.S.

“Can We Pretend” (+’Justments, 1974)

Lush and brutal, “Can We Pretend” is a bright plea for the impossible. Withers asks for the couple to move forward by forgetting about past harm and hurt. “Paint a portrait of tomorrow/With no colors from today” is the particular poetry deployed. No less a giant than Jose Feliciano plays guitar, keeping the energy breezy, but don’t buy it — +’Justments, from which this album comes, came in the wake of Withers’ brief marriage to activist and actress Denise Nicholas. It’s make-believe. — R.S.

“Lovely Day” (Menagerie, 1977)

There was a tenderness about Withers that ensured even when he got funky as on this early 1978 hit, it was never unhinged. “Lovely Day” demonstrates you can get down without getting freaky, and Withers’ warm, reassured croon exudes the wise, tempered joy of someone of someone who’s lived enough life to appreciate the moments of quiet contentment more than the raucous peaks. Speaking of highs, his 18-second sustained note toward the end never ceases to elate and impress. — J. Lynch

“Just the Two of Us” (Grover Washington Jr.’s Winelight, 1980)

Withers lent his silky vocals to saxophonist Grover Washington Jr.’s melodies for this smooth jazz classic. “Just The Two of Us” quickly tapped into everyone’s inner romantic, as the stunning pair-up stayed at No. 2 on the Hot 100 for three weeks and earned a Grammy for best R&B song. As if the record needed to further prove how far its legs could stretch, Will Smith transformed it into a heartfelt rap ode to his son for 1997’s top 20 hit of the same name, while Eminem went down a more haunting route when he interpolated it for “’97 Bonnie & Clyde” for 1999’s The Slim Shady LP. — BIANCA GRACIE

“In the Name of Love” (Ralph MacDonald’s Universal Rhythm, 1984)

Bill Withers’ final appearance on the Hot 100 in his lifetime came this breezy smooth jazz winner front by percussionist and band leader Ralph MacDonald. Like “Just the Two of Us” years earlier — and in fact, the original version of “In the Name of Love” was its Winelight album-mate — Withers sounds overjoyed to be along for the ride here, his grin audible even as he sings about love “jumping up and down on your emotions/ Just another way to break your heart.” The song earned Withers his final Grammy nod for one of his own recordings, nominated for best male R&B vocal performance — though Club Nouveau would get him a third gramophone for his mantle three years later when their version of “Lean on Me” won best R&B song. — A.U.