Many artists aren’t just singing in one style and hoping to make a career out it.

The fences officially have been moved.

When Sam Hunt slid “Hard to Forget” into country radio playlists, he expanded the playing field for the format. On one hand, he introduced modern listeners to Webb Pierce‘s “There Stands the Glass,” a 1953 single that demonstrates the whiny twang that once defined the genre. But he packaged it with start-and-stop, tech-based rhythms that pulled directly from hip-hop.

It’s a stunning development: blending musical sounds that are separated by seven decades on the calendar and perhaps an even greater distance on a sonic map. But it’s also indicative of the increasingly elastic nature of the format. Jon Pardi‘s “Ain’t Always the Cowboy” pays distinct homage to George Strait‘s 1985 hit “The Cowboy Rides Away,” while Carrie Underwood‘s “Drinking Alone” digs into a slow-boiling R&B groove. Dierks Bentley‘s side project, Hot Country Knights, waves a flag for ’90s country, even borrowing its name from the 1991-92 NBC series Hot Country Nights. Meanwhile, Sara Evans — whose first album walked a traditional line — released a covers album, Copy That, on May 15 that runs the gamut from 1950s Hank Williams to 1980s new wave to 1970s Earth, Wind & Fire.

“When I sing ‘I’m So Lonesome I Could Cry,’ I’m like the most country singer you’ve ever heard,” suggests Evans. “But then when I do ‘My Sharona,’ I belong in a rock band. Some days you want to wear jeans and boots, and then other days you want to wear high heels and a skirt.”

Testing musical boundaries always has been in fashion. Patsy Cline blended appreciation for traditional-pop singer Teresa Brewer and Ernest Tubb. Alabama caught flak for having Creedence Clearwater Revival attitude alongside its Merle Haggard influence. And Billy Ray Cyrus used to weld Led Zeppelin‘s “Heartbreaker” onto his live performances of “Achy Breaky Heart.”

All of those developments are examples of how art of any kind progresses. Artists don’t sing a song in one style and hope to make a career of it. They create interest with new music that keeps unveiling new facets, essentially blending their core genre with sounds they found elsewhere.

“The positive things that you grew up on are probably going to be what you try and continue through your whole life,” says High Valley frontman Brad Rempel. “For us, a huge part of what we grew up on was harmony. It was story songs. It was that kind of ’90s country. If you look at our favorite ’90s country bands, they were all the ones that had bluegrass influences.”

Appropriately, the title track to the duo’s new Grew Up on That EP, released May 8, nods to one of its biggest influences with the ultra-hooky chorus line “Ricky Skaggs on the vinyl.” It’s easy to focus on the Skaggs part of that equation, but the back half is just as illustrative. The resurgence of vinyl demonstrates why heritage musical influences often work in new textures. Old material can return under the right circumstances, and that’s usually when it’s cast in a modern context. High Valley’s Skaggs reference is backed by a bouncy, gurgling mandolin part, a different kind of rhythm than the instrument brought to bluegrass.

Finding the right balance of old and new was a challenge for High Valley when it first came to Nashville. Growing up in a very rural Mennonite community in Canada, its members had limited exposure to entertainment. So when they started doing sessions in Music City, they faked their way through it when producers mentioned a non-country sound, such as Pearl Jam or John Mayer. But now the pair brings its own suggestions to the table.

“For every time I play a producer or a co-writer a Diamond Rio or a Shenandoah or a BlackHawk reference,” says Rempel, “I probably also play them Selena Gomez or Post Malone or The Chainsmokers or something because we’ve learned about that stuff since being civilized and getting out into the real world.”

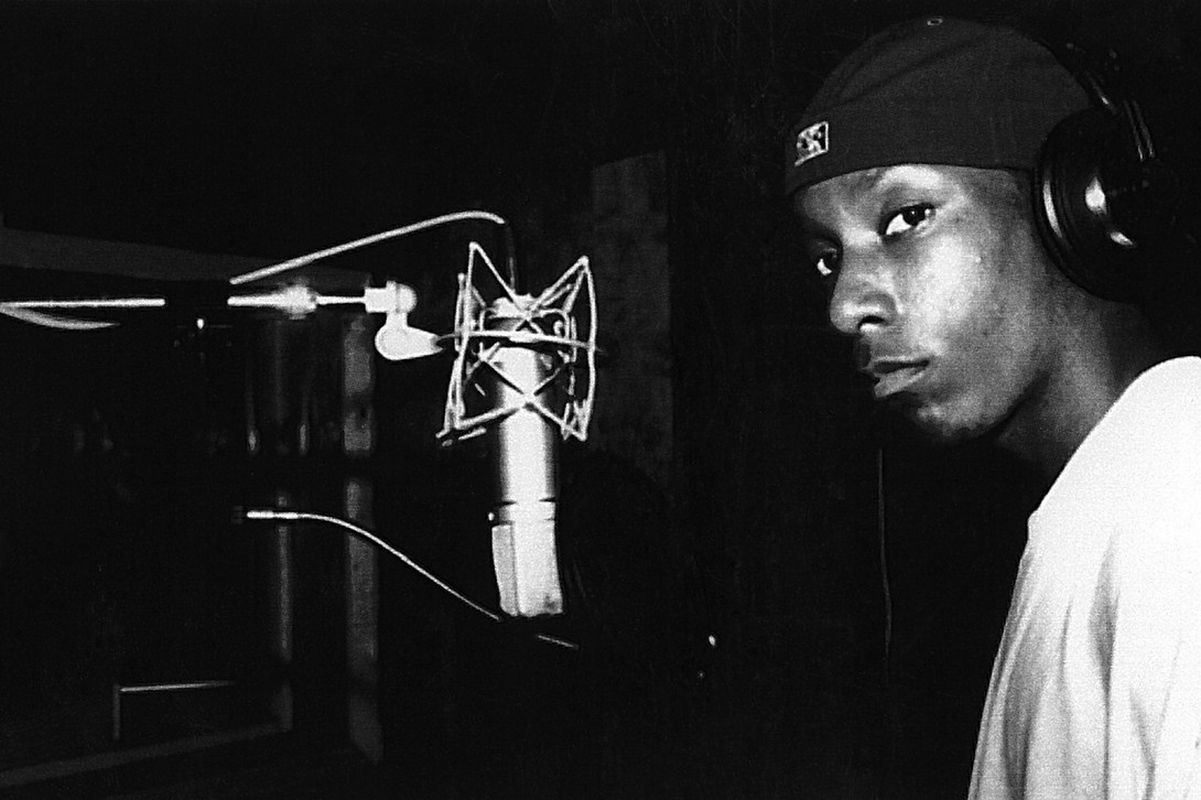

Those atypical sounds help distinguish a country artist. Walker Hayes has employed Macklemore-like phrasing to create a unique presence. His new single, “Trash My Heart,” is fairly light, but he says Macklemore and late rapper Tupac Shakur helped him understand the importance of tackling heavy, vulnerable subjects.

“I’ve actually come to the conclusion that I love things that are kind of uncomfortable to sing about, like things that you might be embarrassed to tell a group about yourself,” he says. “Honestly, that’s probably what the majority of the group is experiencing are those things that you keep quiet in your heart.”

Like Hayes, Hunt has blended country and hip-hop — and has received pushback for it, too — but it’s a mix of music that’s familiar to him and to his “Hard to Forget” co-writers. Ashley Gorley (“Dirty Laundry,” “T-Shirt”) synthesized the music he heard on a variety of Lexington, Ky., radio stations in his youth, while Luke Laird (“Down to the Honkytonk,” “Undo It”) took in multiple formats in the Pittsburgh area. It was Laird’s idea to sample “There Stands the Glass,” though it resonated with everyone involved in Hunt’s hit.

“Of course, I love traditional country music,” he says. “But growing up in high school in the ’90s, now I realize what attracted me to the ’90s hip-hop was the production and the samples. This song is a perfect mix of my influences because I’m so influenced by ’90s country and ’90s hip-hop, and this combines all of that.”

Country’s future should thus be interesting. Teens in 2020 are hearing Pardi’s Strait-influenced single, Underwood’s urban-tinged title and Hunt’s blend of really old country and very modern rhythms. And they’re building playlists that also feature modern pop, classic rock and hip-hop. There are tons of creative approaches that can work in the genre; it probably has fewer limitations than at any other time in its history.

“I love that,” says Evans. “That’s the way it should be.”

This article first appeared in the weekly Billboard Country Update newsletter. Click here to subscribe for free.