Africa’s acts are bigger than ever. Now it needs venues to match.

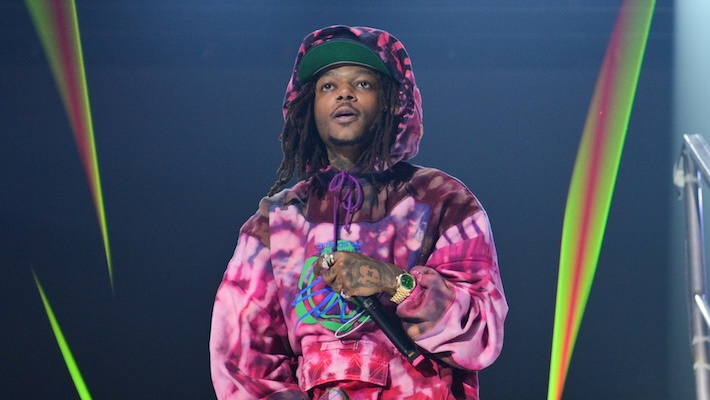

Nigerian Afrobeats star Naira Marley has become so popular internationally that his home country — Africa’s largest, with a population of over 205 million — doesn’t have a live venue large enough to contain his burgeoning fan base.

Overseas, the 26-year-old artist’s popularity expands far beyond West Africa’s diaspora. In 2019, he sold out London’s 4,900-capacity O2 Academy Brixton in under three minutes for a show in February, and he’s considering playing an arena when he returns.

“In the [United Kingdom], he would graduate to the next venue size,” says Chinedu Okeke, promoter-creator of the Gidi Culture Festival in Lagos, Nigeria, which launched in 2014. “But [here], there’s not really anywhere he can do his own show beyond a 5,000-capacity venue, because they just don’t exist right now.”

The soccer-crazy nation has plenty of stadiums, but Okeke says the venues aren’t suitable for most concerts.

The eventual debut of the Basketball Africa League, a joint venture of the NBA and the International Basketball Federation, may lead to the construction of new venues, but for the time being, there are few options for arena-ready acts. South Africa, home to the continent’s three biggest markets — Johannesburg, Durban and Cape Town — has six arenas, as well as the region’s largest promoter, Live Nation-owned Big Concerts, which makes the country Africa’s top touring destination.

The continent’s robust festival scene is another option for artists with Marley’s star power. Gidi Culture Festival, which typically draws 10,000 fans in April, was supposed to be Marley’s unofficial homecoming show until the pandemic shut down the live industry. (Gidi has been tentatively rescheduled for October.)

When concerts and festivals do resume in Africa, the underlying problem will remain: A growing number of artists, including Burna Boy, Wizkid and Davido, are playing to increasingly larger crowds in Europe and U.S. cities like Houston and Atlanta, but face challenges touring back home.

“Africa hasn’t historically been a hard-ticket market,” says Okeke, explaining that much of the live-music business is driven by consumer brands like Coca-Cola that design and promote their own events, usually festivals. They pay artists a set fee and fund other aspects of the event, which “helps keep the ticket price low,” says agent Joe Hadley of Creative Artists Agency, whose Jamaican artist client Koffee has played the festival circuit there.

Most festivals take place in December and January (the Christmas season) or midspring (Easter) and are anchored to major hubs: Gidi in Lagos; Afrochella in Accra, Ghana; Blankets & Wine and Africa Nouveau in Nairobi, Kenya; the Lake of Stars Festival on Lake Malawi; and Rocking the Daisies in Johannesburg and Cape Town.

Despite the popularity of this model, Okeke says it “limits artists’ ability to tour more frequently and gradually grow their fan base.” If Africa’s recorded- and live-music businesses are to evolve, he says investment in both club- and arena-size venues is needed throughout Africa, especially in Nigeria and other countries in West Africa.

Developing artists need smaller venues to build their fan bases, and one company answering the call is Vivendi-owned CanalOlympia, which operates a network of 14 venues in western African countries including Senegal, Cameroon and Ivory Coast, as well as Madagascar. CanalOlympia’s modular spaces — which are geared for those regions’ rapidly growing middle-class populations — convert from indoor 300-capacity movie theaters to open-air stages that can accommodate several thousand fans. They are equipped with modern audiovisual technology and can run on hybrid battery and solar-power systems.

Touring acts still have to navigate the many difficulties of traveling between countries in Africa, however. Playing a series of CanalOlympia venues requires a combination of commercial and chartered flights and bus travel, and the availability of backline varies from city to city — logistical issues that favor smaller groups and solo acts. And only six of those venues are in countries that belong to the Economic Community of West African States, which allows travel and work among member nations without a visa.

In spite of these challenges, “more artists now see Africa as a touring destination,” says Sipho Dlamini, Universal Music Group managing director of South Africa & sub-Saharan Africa. “We’ve had a number of conversations with Universal artists from the U.S. who want to tour Africa” instead of just playing South Africa and heading home.

To that end, Okeke says he’s in the early stages of working with a public-private partnership on an arena project in Nigeria. “If we really want to be a global touring market, we need a venue capable of hosting the large touring shows,” he says.

A venue in Nigeria would connect the country to a cross-continent touring route of modern arenas built in the last decade that includes Kasarani Safaricom Indoor Arena in Nairobi and Le Palais des Sports de Libreville in Gabon. He envisions a future in which a network of 10 to 12 arenas puts countries like Burkina Faso and Benin, which are adjacent to Nigeria, on touring routes.

YouTube director of urban music Tuma Basa says he’s confident that the BAL will lead to the construction of arenas. Basa, whose family hails from Rwanda, points to its capital city, Kigali, where construction on East Africa’s largest arena — a joint venture between the Rwandan government and Turkish real estate development/construction company Summa — wrapped in 2019. Kigali Arena is home to the Patriots Basketball club, one of 12 teams that compete in seven host cities, including Dakar, Senegal, and Luanda, Angola, which are each home to modern arenas built after 2016. While league officials haven’t said much about the construction of new venues since the inaugural season was postponed in March due to the pandemic, Lagos is one of the BAL’s host cities and will likely need a new home to replace the sports facilities at Nigeria’s National Stadium.“It’s going to improve,” says Basa of Africa’s touring challenges, adding that he knows people “who are looking at building midsize infrastructure.”

Okeke observes that the economic benefits would extend beyond the music industry. “An arena is important for touring, but it’s also a milestone for development,” he says. “It’s going to take more than the music community to get it done. We will need the support of the government to lead finance and development, and recognize the importance of investing in ourselves.”

A version of this article originally appeared in the May 23, 2020 issue of Billboard.