On Wednesday, New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio became the latest public figure to reference John Lennon’s “Imagine” during turbulent times. When countering calls for police reform, de Blasio mentioned the enduring rock standard; the latest example of how notables have co-opted its lyrics for their own agendas.

Journalist Jack Mirkinson tweeted de Blasio’s full comments, in which the mayor compared calls to defund the police to the lyrics of the popular song. “I’m reminded of the song ‘Imagine’ by John Lennon,” de Blasio began during the Wednesday press conference. “I think everyone who hears that song in its fullness thinks about, ‘What about a world where people got along differently? What about a world where we didn’t live with a lot of the restrictions that we live with now?’ But we’re not there yet.”

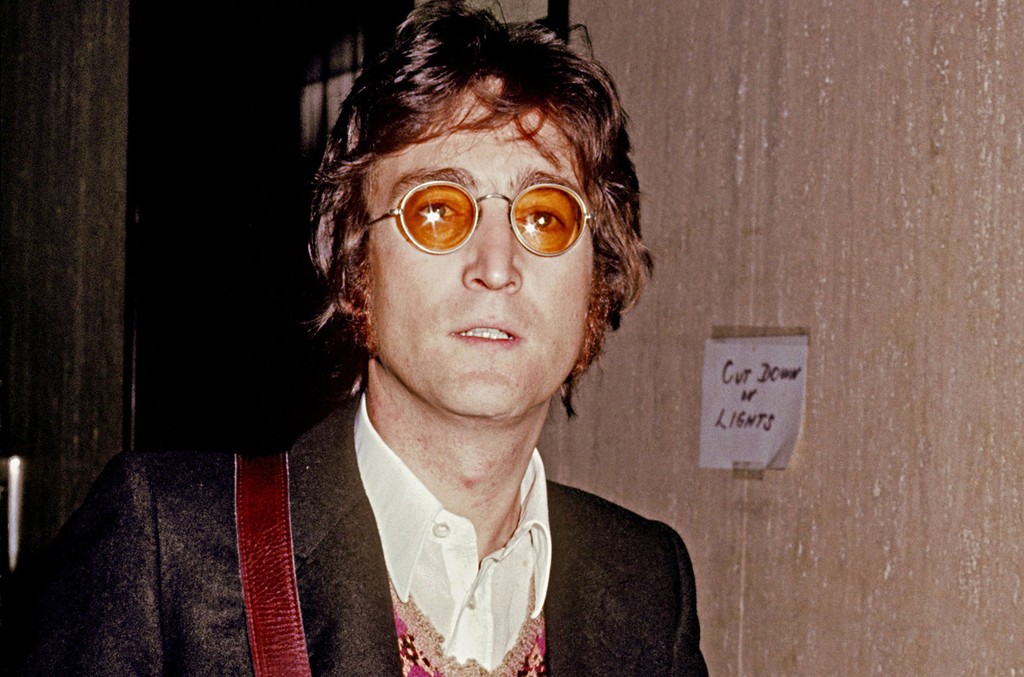

“Imagine” has remained a cultural fixture in the almost 50 years since its 1971 release. The late former Beatle’s solo discography often languishes in the sizeable shadow of that band’s unprecedented accomplishments, but “Imagine” transcends, in many ways, even the most popular hits by the Fab Four. It works as both a call for togetherness and as an admonishing of what causes divisions; making it suitable for unifying poses and calls for reassessment/reform across generations. But as de Blasio’s statements illustrate, it’s also become the kind of simplified quasi-anthem that gets repurposed and reinterpreted depending on who’s talking.

And let’s be honest, “Imagine” has as many detractors as fans — especially since it is so susceptible to grandstanding and pandering. The song had already become a topic of scorn once this year, when Hollywood A-listers led by Wonder Woman star Gal Gadot participated in an online singalong of the tune this spring. Meant to foster a “we’re all in this together” sentimentality as millions grappled with the isolation of quarantine during the global coronavirus epidemic, it instead sparked widespread annoyance.

“It was an awful rendition, but they might have been doing it for good reasons, to help these normal nobodies,” comedian Ricky Gervais said of the singalong during an interview with BBC Radio 5 Live in May. “But they’re going, ‘My film’s coming up and I’m not on telly – I need to be in the public eye’ – not all of them, but some of them.”

“Imagine” has become a song all too often used to condescend in times of struggle, especially when it’s being used by major corporations or Hollywood celebrities whose very careers are predicated on so many things the song supposedly asks us to consider a world without. Since its 1971 release, the piano-driven ballad about an idyllic world with “no possessions” and “no religion” has been derided as an empty platitude, written by a hypocritical millionaire rock star. It’s also been blasted by more conservative-leaning personalities as an ode to communism, something that has only galvanized its use as a middle finger for left-minded people aimed at the right.

“Imagine” had its genesis in words written by Yoko Ono, namely her poem “Cloud Piece” included in her 1964 book Grapefruit. The song was also partially inspired by a Christian prayer book Lennon had gotten from comedian Dick Gregory.

“Dick Gregory gave Yoko and me a little kind of prayer book,” Lennon told David Scheff of the song’s origins during his infamous 1980 Playboy interview. “It is in the Christian idiom, but you can apply it anywhere. It is the concept of positive prayer. If you want to get a car, get the car keys. Get it? Imagine is saying that. If you can imagine a world at peace, with no denominations of religion – not without religion, but without this my-God-is-bigger-than-your-God thing – then it can be true.”

The song has since been covered by an endless list of notable musicians; Joan Baez, Herbie Hancock, Diana Ross, Liza Minnelli, Neil Young and Emeli Sande have all offered a rendition at some point or another. It’s been a feature at every Lennon tribute over the past near-40 years and made an appearance during the 2012 Summer Olympics in London; Lady Gaga performed it at the opening ceremony of the 2015 European Games.

The Imagine album, also released in 1971, came as a semi-reaction to Lennon’s more abrasive, less-accessible proper debut album John Lennon Plastic Ono Band. Released the year before, that project was sparse and infamously personal, with the singer-songwriter delving deep into his own perspective and history on tracks like “Mother” and “Working Class Hero.” Freed from having to compromise his own voice to be “Beatle John,” Lennon took the opportunity to lay bare his emotions regarding his own childhood and image. Though it wasn’t a huge commercial success (particularly by Beatles standards), it became the most critically-acclaimed album he would release in his solo career.

“’Imagine,’ both the song itself and the album, is the same thing as ‘Working Class Hero’ and ‘Mother’ and ‘God’ on [Plastic Ono Band],” he would say later. “But the first record was too real for people, so nobody bought it. It was banned on the radio.”

On his second album, Lennon clearly sought to craft something more commercial and appealing to mainstream Beatles fans. Although both Plastic Ono Band and Imagine were produced by notorious superproducer Phil Spector, the latter is a much more polished affair. And in the title track, Lennon offered the kind of paean that fans of his old band would fawn over — and a song that would spend the next several decades becoming an even more watered down representation of itself.

“Anti-religious, anti-nationalistic, anti-conventional, anti-capitalistic, but because it is sugarcoated it is accepted,” Lennon was quoted as saying in Geoffrey Giuliano’s 2000 biography Lennon In America. “Now I understand what you have to do. Put your political message across with a little honey.”

It’s a song that was almost destined to turn into what it’s become today. In many ways, the track epitomizes the sanitizing of Lennon as a persona and public figure; controversial ideas couched in a likeable melody — and a more saccharine distillation of what was a very complex and contradictory oeuvre of topical music on a wide range of issues. Within a year of its release, Lennon and Yoko Ono would drop the much more controversial political concept album Sometime In New York City, which included the lightning rod “Woman Is the N—er Of the World” and songs in support of activists on the left like Angela Davis and John Sinclair. Those songs are a lot less singalong friendly.

“The peaceful protest is the essence of how we make progress, the reforms made within the NYPD are progress, deep progress,” de Blasio said Wednesday in his “Imagine” harangue. “But for folks who say, ‘Defund the police,’ I would say that this is not the way forward.” Evoking “Imagine” to dismiss the idea of defunding police reveals how seriously (or not seriously) de Blasio takes the grievances aimed at police departments. Not only has the song become a go-to anthem for the detached, a song that asks that we imagine a world with no differences as opposed to challenging us to see each other fully but without hate, but it has also been distorted here for the purpose of squelching concerns about law enforcement institutions that are very likely irrevocably broken.

Maybe it’s appropriate that a song this mawkish and convenient is re-molded so often; considering the all-too-tidy image of John Lennon-as-hippie-messiah has always itself been revisionist. But a “better world” is one that looks at the warts, and takes them seriously. Bill de Blasio missed an opportunity to examine glaring institutional ugliness, and instead chose to reference a song that never really had any answers. Maybe we should find another to evoke in times like these — there’s always “Freda Peeple.”