Neil Peart was an extraordinary being sent to Earth to destroy drummer jokes. Drummer jokes, if you’re not familiar, are a subcategory of music nerd humor that lampoon the least melodic, least theory-driven member of most bands (bassist jokes also exist, for what it’s worth). For example: What do you call someone who hangs around musicians? A drummer. Or: What do you call a drummer with half a brain? Gifted.

All the negative stereotypes of rock drummers — that they exist only to keep time, that they don’t contribute to composition, that they don’t write lyrics, that they get by on brute force rather than elegance — wither and die in the shadow of Neil Peart. The longtime Rush drummer, who died at 67 this week following a three-year battle with brain cancer, smashed all previous perceptions of rock drummers and redefined the capabilities of two sticks rhythmically hitting flat surfaces.

Peart joined Rush between their first and second albums, and the changes in lyrical depth and compositional ambition were immediate. The trio's 1974 self-titled debut (with original member John Rutsey on drums) is a blues-based hard rock album that slots nicely alongside contemporaries like Wishbone Ash or Savoy Brown, but there’s not much in the way of distinguishing features, or much outside of Geddy Lee’s shrill tenor that resembles the since-established Platonic ideal of Rush. The following year’s Fly By Night, their first with Peart after Rutsey's departure, was still a far cry from the feats of head-swirling songcraft that Rush would later achieve, but still sounded like the work of an entirely changed band.

Kicking off with a tricky 7/8 time signature, Fly By Night roped in plenty of additional hallmarks of ‘70s progressive rock, including themes ripped from literature (Tolkien on “Rivendell” and Ayn Rand on “Anthem”) and multi-part epics (“By-Tor & the Snow Dog” contains four distinct, labelled sections). The only added variable was Peart. He wasn’t a practiced lyricist — Lee asked him to assume writing duties because, as the singer/bassist put it, “This guy reads a lot, he has a great vocabulary, and I hate writing lyrics”— but his newfound ability to do so freed up his bandmates to focus on composition. What’s more, his technical prowess then allowed those compositions to extend far beyond the confines of blues rock’s cyclical, repetitive structures.

The band’s label, Mercury, might not have been happy with the departure from Rush’s more tried-and-true formula (in a 2013 interview, Lee recalled their response: “This is not the same — what is this ‘By-Tor’ shit?”) but Fly By Night set the blueprint for the band’s success. By penning the catchy, enduringly popular title track as well as the adventurous “By-Tor,” Peart began carving out a niche within the then-booming prog world. While capable of dazzling complexity, he never used it to obscure a song’s melody or its structure, as many accomplished wizards of prog, math rock, and metal have. And while clearly in possession of an anthemic, pop-friendly pen — Rush songs have hooks, baby — he never gave into all-out accessibility. To put it plainly, you can sing along to Rush (even their instrumental songs!), but tapping your foot in time with Rush presents a much greater challenge.

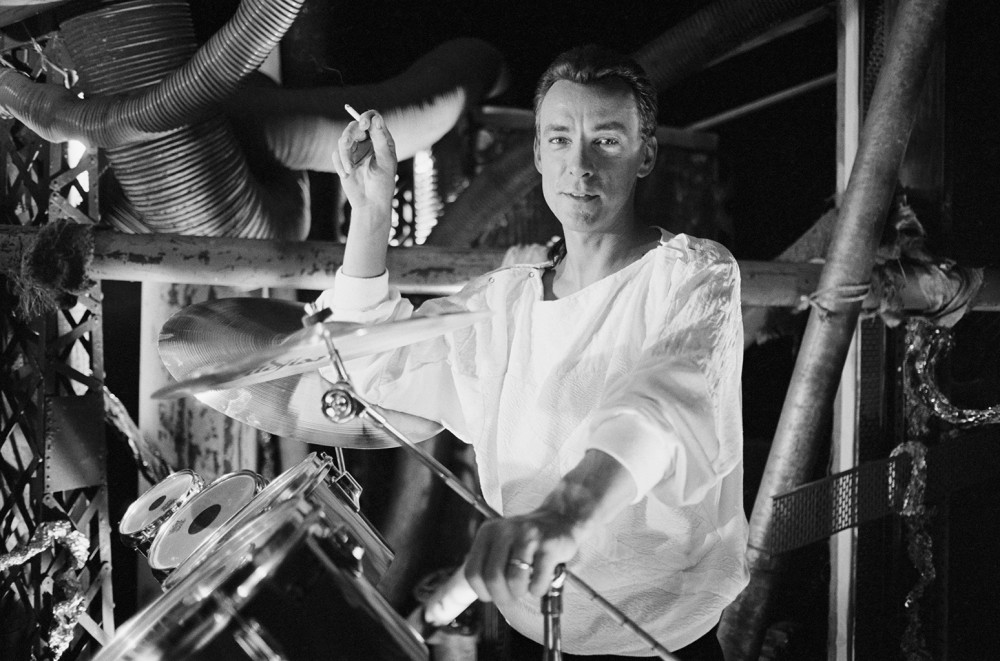

Complexity, depth, and headiness on one side, catchiness, positivity, and popularity on the other. Not many artists can balance that precarious scale, and those that do are routinely lambasted by critics and discerning listeners (see: every jam band ever). The same was true for Rush, especially Peart. Just the way he looked onstage, surrounded by his (in)famous 360-degree drum kit, outfitted quite literally with bells and whistles galore, is rife for This is Spinal Tap-style ridicule or austere punk rock backlash. In many ways, Peart was the embodiment of the ‘70s and ‘80s prog excess that, with its many-synthesizer arrays, highfalutin concepts, and self-seriousness, turned off generations of boomer purists and disillusioned Gen X-ers.

But despite the way he appeared onstage, a solemn figure behind a fortified temple of shiny hardware that costs more than your life savings, Peart was so devoted to craft over empty extravagance. Listen to his beats. They often start off sounding simple, familiar… until there’s that unexpected extra beat, or that unexpected missing beat, at the end of a measure. He’s not Tool’s Danny Carey (a god-tier drummer in his own right), using complex polyrhythms that weave in and out of the song’s central groove — Peart’s playing always looked forward, guiding songs along from movement to movement. And while he may have had at least a dozen toms and cymbals, he uses each purposefully, picking specifically-tuned ones at specific moments during specific sequences. It’s not out of convenience, as it is for so many drummers who’ll reach for the cymbal closest to the tom they just hit — it’s out of sheer melodic will.

Peart’s uplifting, clear-eyed lyrics are championed by Rush fans as well as the wellspring of metal and alt-rock acts Rush inspired, but they’re reviled by others. In 2007, Blender named Peart the second-worst lyricist in rock history (behind Sting). Under the header “An ace on the rototoms, a train wreck on the typewriter,” the now-defunct publication called epic-length Peart compositions like “Cygnus X-1” “richly awful tapestries of fantasy and science fiction, steeped in an eighth-grade understanding of Western philosophy.”

Peart certainly did have a penchant for rather silly mashups of mythology, religion, philosophy, fantasy, and sci-fi— just look at the “Cygnus X-1” suite’s tale of spaceship going through a black hole and coming out amid a war between followers of Apollo and Dionysus (or something?). He was, however, at least a bit conscious of how abstract and nerdy it all was, which is more than you can say for many of his prog peers. A few songs after “Cygnus” on 1978’s Hemispheres is a song subtitled “(An Exercise in Self-Indulgence).” And it’d be remiss not to mention Rush’s 2012 swan song, Clockwork Angels, here, as it’s one of the most graceful, least over-labored concept albums in prog history.

Another much more reasonable critique of Peart’s writing concerns his affinity for Ayn Rand. Both the aforementioned “Anthem” and the iconic “2112” suite are loosely based on Rand’s novella Anthem, and Peart gave plenty of interviews about the libertarian beliefs the author inspired in him. In 1978, NME’s Barry Miles infamously drew parallels between “2112” and the radical right, writing that Rush preached “what to me seems like proto-fascism.”

That’s a pretty rich reading of Peart’s quaint sci-fi tale of an individual finding an electric guitar and defying a totalitarian regime, but there are other moments in Rush’s discography that could feasible rankle the left. Take 1980’s “Freewill,” which is over-archingly about relying on the self over religion, but contains some almost “Welfare Queen”-style conservative rhetoric against, “…Those who think/ That they were dealt a losing hand/ The cards were stacked against them.” That’s a little harsh!

In more recent years though, Peart recanted on his youthful Rand obsession. When asked by Rolling Stone in 2012 if the author’s words still “spoke to him,” Peart gave a very thoughtful answer:

Oh, no. That was 40 years ago. But it was important to me at the time in a transition of finding myself and having faith that what I believed was worthwhile… For me, it was an affirmation that it’s all right to totally believe in something and live for it and not compromise. It was a simple as that. On that “2112” album, again, I was in my early twenties. I was a kid… Libertarianism as I understood it was very good and pure and we’re all going to be successful and generous to the less fortunate and it was, to me, not dark or cynical. But then I soon saw, of course, the way that it gets twisted by the flaws of humanity.

If you’ve paid attention to Peart’s lyrics as a whole, this response makes much more sense than some affirmation of neo-facsism. It’s what Peart was at his core — an optimist. Beyond the idealistic parables and sometimes-clumsy combinations of folklore and fantasy, the pure positivity of Peart’s writing is what truly shines.

One of Rush’s all-time biggest hits, “The Spirit of Radio,” paints recorded, mass-broadcasted music as a magical force: “Invisible airwaves crackle with life/ Bright antenna bristle with the energy/ Emotional feedback on timeless wavelength/ Bearing a gift beyond price, almost free.” It’s corny, it’s earnest, it’s beautiful. And just when you think Peart’s slipping into nostalgic rockism, he comes through with, “All this machinery making modern music/ Can still be open-hearted/ Not so coldly charted/ It's really just a question of your honesty.”

Peart, as the band says in the next line of “The Spirit of Radio,” liked to believe in the freedom of music. “Art as expression,” he wrote on another cut from 1980’s Permanent Waves, “Not as market campaigns, will still capture our imaginations.” That reads like a punk song, but it’s a song by Rush, a band that punk ostensibly rose in opposition to. That’s a microcosm of Peart as a whole: blown up as a poster child for hulking, unsexy cultural relics like PROG, FANTASY, LIBERTARIANISM, but in truth, just a relentlessly talented dreamer beholden to none of the labels people ascribed to him.