"I am not guilty of this, and I need to move on with my life," says the non-binary rocker whose new single, 'Laugh Track' and upcoming album were inspired by the whiplash experience of their band's abrupt cancellation

Out of work as a musician, living in a tiny Brooklyn apartment and severely depressed, Ben Hopkins wrote an entire album in a windowless bedroom in late 2017. “Somebody swallowed the sun/Now the morning never comes,” Hopkins sings on “Internet Song,” which is built around a single G-chord that sounds like Kurt Cobain at his most furious. “They put the Internet in the sky/Now I’ll stare at it till I die.”

“I was in a really bad state of mental health — a complete state of suicidal ideation,” says the former singer, guitarist and occasional drummer of the DIY punk duo PWR BTTM, staring into a webcam during a Skype video call. Hopkins, who is non-binary and uses they/them pronouns, pauses to remove a baseball cap and run a hand through a dark forelock before putting on a different cap. The song, they continue, is “a keyhole into the true essence of what I was feeling. All of a sudden — in a weekend — this is my new reality forever because I’ve been canceled or whatever? This is what I have to look forward to until I’m dead?”

In early May 2017, Hopkins and bandmate Liv Bruce were poised for a career breakthrough. A week before PWR BTTM was to release its second album, Pageant, Vice’s music site Noisey declared them “America’s Next Great Rock Band,” and in the days that followed, NPR shined a spotlight on the duo by featuring an advance stream of the record on its website, The New York Times readied a profile, and Rufus Wainwright interviewed them for Billboard.

By mid-May, as Hopkins put it, PWR BTTM were canceled. A series of mostly anonymous social media posts accused Hopkins of rape, assault, “inappropriate sexual contact,” being a “known sexual predator” and “an abuse apologist.”

The allegations, which materialized on May 11, the eve of Pageant’s release date, were especially shocking given the safe community that PWR BTTM had built — and which Hopkins had often extolled onstage — as the band rose through New York’s club scene and began to tour outside the city. “For the queer community and the trans community, you can’t just go anywhere and feel at home or feel accepted or feel seen,” says Sarah Marloff, a Washington, D.C., writer who covers LGBTQ issues and sexual assault. “I saw PWR BTTM and it felt safe. It felt fun. It felt like ours.” For some, the allegations against Hopkins felt like a betrayal of those ideals. “It’s hard when you’re like, ‘You made me trust you,’ and I don’t trust people easily,” Marloff says. “You were fighting for the right causes, and then you took advantage of someone.” She pauses, then adds: “Allegedly.”

The women’s lifestyle website Jezebel amplified the accusations in a May 12 story alleging Hopkins “perpetrated multiple assaults, bullied other people in the queer community and…made unwanted advances towards underage minors.”

By May 15, PWR BTTM had been dropped by Polyvinyl Records, the label that was set to distribute Pageant. “There is absolutely no place in the world for hate, violence, abuse, discrimination or predatory behavior of any kind,” read the indie label’s statement. “In keeping with this philosophy, we want to let everyone know that we are ceasing to sell and distribute PWR BTTM’s music.” The album was pulled from streaming platforms, and the band’s first LP, Ugly Cherries, was also removed from distribution by another label. Salty Artist Management dropped the duo, the Hopscotch Festival canceled a scheduled showcase for the band, and PWR BTTM’s tour was canceled after fellow indie artists Nnamdi Ogbonnaya, iji, T-Rextasy and Tancred dropped off the bill. T-Rextasy followed up with an elaborate Twitter thread, saying it had “made a mistake supporting this band” and “we feel that we may not be the only ppl in this community to have heard these allegations before today.”

Later that fall, the #MeToo hashtag would go viral when the Times and The New Yorker after months of chasing down rumors, reluctant sources (and the details of at least one police investigation) published damning investigations into allegations of rape and other sexual misconduct against movie mogul Harvey Weinstein. By comparison, Hopkins and PWR BTTM were canceled in the span of roughly one week based on a handful of anonymous allegations and tweets.

Other public figures with higher profiles and known accusers — Chris Brown, Robin Thicke, Supreme Court Justice Brett Kavanaugh and President Donald Trump, to name a few — have been allowed to carry on their careers despite allegations of sexual misconduct. The claims against Hopkins are unusual and frustrating, in part, because they’re anonymous — and those who made them have chosen to remain silent. After more than three years of pondering the path forward, Hopkins is prepared to fight for a second chance. “I am not guilty of this,” they say, “and I need to move on with my life.”

Hopkins says the 2017 allegations left them shocked, then numb. They consulted lawyers to determine if there was any legal recourse against the labels and managers that dropped the band, but decided against it, explaining, “It was all very speculative, and I did not want to put my family through a $150,000 lawsuit.”

In the aftermath, Hopkins and Bruce separated, the former traveling to their hometown of Hamilton, Massachusetts, to live with their parents before returning to New York a few months later. This was a months-long period of “very, very low moments and self-harm,” Hopkins says. “I was not well. I felt like nothing existed.”

Eventually, Hopkins began to write music again, much of it inspired by the whiplash experience of PWR BTTM’s abrupt cancellation and the emotions they experienced during that time.

The result is their solo debut, i held my breath for a really long time once.

Unlike PWR BTTM’s campy punk sound, with its shades of Tune-Yards and (even) They Might Be Giants, i held my breath roars with ‘90s guitars, set against Hopkins’ playful, theatrical and high-pitched voice. The lyrics are oblique and freighted with pain and weariness: “Tired of being tired!” Hopkins repeats throughout the talky, seven-and-a-half-minute “Laugh Track,” which is the album’s first single. Another song, “Sister,” appears directed at someone who may have been involved in PWR BTTM’s downfall:

Try and recall how it used to be

Before the summer

When there was a sense of possibility

And you and I like sisters

Everything felt alright

Little did I know about the fire on your mind

Now I am burning

Why in the hell were you lying?

The plan is to release the album sometime this fall. In the meantime, “Laugh Track,” which was released shortly after midnight on July 3, will serve as a test of sorts to see if fans of PWR BTTM will embrace Hopkins once again.

‘I Felt Uncomfortable About the Energy They Were Giving Me’

One person who contends Hopkins deserves a second hearing is their new manager, Lisa Barbaris, who for 20 years has represented LGBTQ heroine Cyndi Lauper. (Pose and Kinky Boots star Billy Porter is also a client.) Initially a fan of PWR BTTM, Barbaris says she was convinced Hopkins and Bruce were “the first queer band that was really going to break that glass ceiling” and become “big, big stars.” (At one point, she attempted to book the duo on Lauper’s annual True Colors United fundraiser for LGBTQ homeless youths, but they were too busy.)

Barbaris, who, with Lauper has lobbied politicians for years to combat hate crimes, workplace discrimination and “don’t ask, don’t tell,” was “disappointed” when she read about the accusations against PWR BTTM. She felt the band deserved due process. “They went from being adored to being hated,” says Barbaris. “It was also the beginning of #MeToo, which I 1,000% support,” she adds. “I believe women, but I believe Ben is telling the truth.”

Barbaris originally wanted Hopkins to write a first-person account of their 2017 experience as an op-ed for this outlet. Billboard’s editors suggested instead a reported story in which Hopkins as well as their accusers would be given the opportunity to tell their respective accounts.

Hopkins agreed to be interviewed, and over the course of two Skype calls that totaled more than two hours, talked about the events that led to their and PWR BTTM’s cancellation.

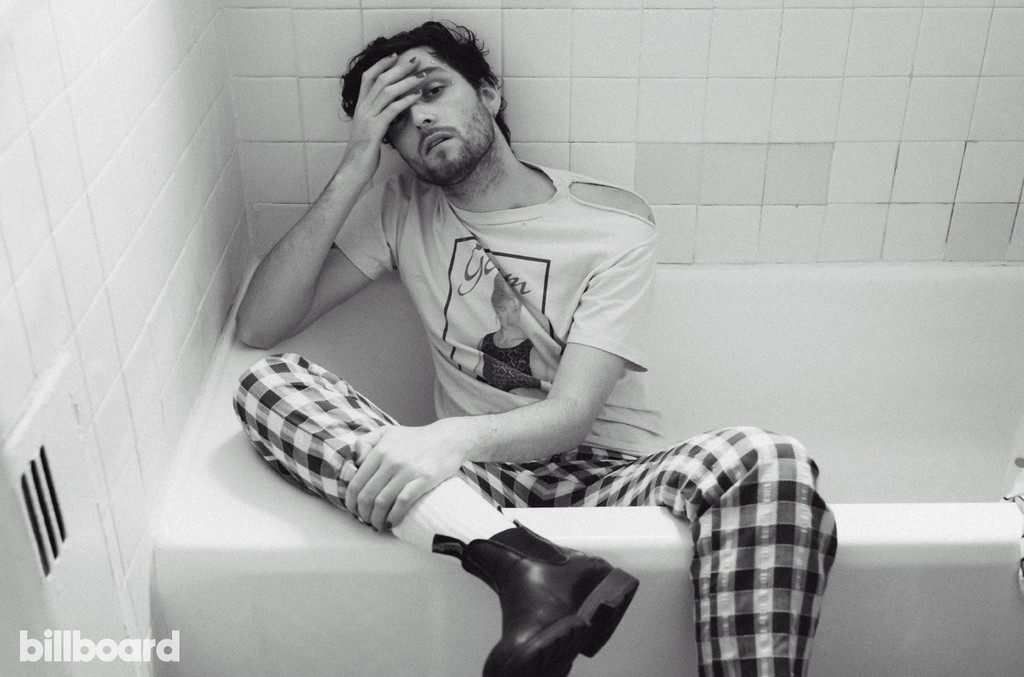

Hopkins, now 28, is skinny, with intense brown eyes, a long nose and a theatrical charisma suited for rock ‘n’ roll, but unlike PWR BTTM’s heyday, when they would perform in tight, shiny dresses, their face smeared with colorful makeup and glitter, they appear on camera unadorned save for nail polish — a different color for each Skype session. During the interviews, Hopkins, at one point, changes sweaters mid-conversation, and, more than once, talks about the tattoos that peek out from underneath their t-shirt sleeves. There’s one of Amy Winehouse and another of the playwright Charles Ludlam, who is name-checked in “Laugh Track.” (“Like Charles Ludlam/As he died of AIDS/As he thought of a script/To a brand new play”)

During the second Skype interview, Hopkins takes nearly 40 minutes to methodically recount the events that they say, led to the barrage of accusations in May 2017. Although it is more detailed, the account does not differ much from the one that Hopkins offered in a May 18 Facebook post.

PWR BTTM in 2013 after Hopkins and Bruce met at Bard College in Annandale-on-Hudson. Both had dressed in drag for a play there, and, as their friendship grew, Bruce, who was in the process of transitioning, floated the idea of starting an all-queer rock band. Hopkins, who says they didn’t identify as queer until “super late in life,” responded, “That sounds terrifying. Let’s do it.”

PWR BTTM’s ascent to indie stardom happened relatively quickly. The band’s first album, 2015’s Ugly Cherries, was critically acclaimed — NPR called the duo “a Trojan horse infiltrating rock stereotypes with inclusive, campy identity politics.” Meanwhile, their live shows — which established Hopkins and Bruce as descendants of The New York Dolls and rock’s first openly trans singer Jayne County — began to sell out. Most media outlets referred to PWR BTTM’s scene as “queercore,” but Hopkins associates that term with an earlier genre, covering ‘90s punk bands like Pansy Division. They prefer “DIY hardcore.”

In March 2016, PWR BTTM toured the country, and like many up-and-coming indie bands, frequently stayed at supporters’ houses while on the road. During a stop in the Midwest, one of those houses hosted a party for the band, where Hopkins met a woman who chatted with them amiably about punk bands. They exchanged phone numbers and she invited Hopkins to hang out at a local dog park the next day, then have brunch with friends.

They spent all day together, and after PWR BTTM’s show that night, Hopkins says they received a 2 a.m. text from the woman inviting them to her house — where they hooked up, “We had great, pleasurable sex on both sides with lots of communication, with both partners involved,” the singer recalls. They kept in touch via text, and the woman later asked Hopkins if she could stay at their small Brooklyn apartment. Hopkins agreed, but says they were distracted with preparations for another series of live dates.

“As soon as they got there, I felt uncomfortable about the energy they were giving me,” Hopkins says of the visitor, adding that gradually, their relationship strained. Initially, Hopkins says the woman initiated sex at the apartment, “but we stopped because I was uncomfortable.” When it’s pointed out that this part of his account differs from the May 18 Facebook post, Hopkins says that over the next few days, they did have sex a number of times (which does jibe with the entry).

When PWR BTTM hit the road, Hopkins says the two continued to flirt via text and met briefly at one of PWR BTTM’s New York shows. The woman was writing an online article about touring queer bands and, Hopkins says, requested their help. When the article posted, PWR BTTM was included with the acts Hopkins suggested.

‘People Are Saying Stuff About You Online’

In January 2017, Hopkins became the subject of a different kind of controversy they admit was self-inflicted. At 19, they had posed for a photo that depicted them smiling next to a swastika they had drawn on the beach. “Back then, I thought being offensive was like being subversive, but in reality it just hurt people,” Hopkins says. “I was young and dumb and should have never done it.”

After the swastika photo hit the Internet, Hopkins says the woman remained friendly. She even asked them to intervene with another person that she accused of sexual harassment. (Hopkins says they provided guidance on how she should deal with the situation.)

Hopkins says they first learned of the allegations of sexual abuse and predatory behavior on May 6. While celebrating a friend’s birthday at a New York City bar, a text arrived: “Hey, Ben,” it read, “people are saying stuff about you online.”

“I was completely and utterly blindsided,” says Hopkins.

On May 12, the Jezebel article expanded upon the social media accusations, with the writer alleging Hopkins “perpetrated multiple assaults, bullied other people in the queer community and…made unwanted advances towards underage minors.” The most serious and coherent charge centered on one encounter: Identified by the pseudonym “Jen,” the woman told Jezebel that, while intoxicated, Hopkins allegedly sexually assaulted her twice in one night and later sent her nude photos.

“I just felt totally powerless in the situation, first due to physicality because they are so much bigger than me in size — and also social status,” said Jen.

Shortly after the Jezebel post, Hopkins read a Facebook entry mentioning the accuser’s hometown and says they became convinced that Jen was the woman they had met at the Midwest house party. “I was like, wait a minute, I didn’t bring this person back to my house like it says in the article. I went back to their house at their invitation,” they say, then referring to their later rendezvous in New York, “If I’m this big, [imposing] person who you don’t feel safe with, why do you want to come stay at my house?”

The floodgates opened. Although the only specific allegations against Hopkins came from the pseudonymous Jen, a Chicago punk scene regular named Kitty Cordero-Kolin began tweeting what she claimed were others’ anonymous complaints about Hopkins. “Ben has violated their autonomy and or consent,” read one; another, “they abused a lot of my friends.” One of the quotes Cordero-Kolin passed along accused Hopkins’ father of making “inappropriate advances on women.” An anonymous accuser opened a Twitter account, @PWRBTTMReceipts, to respond to everything the band’s principals said or did.

Hopkins and Bruce arranged a conference call with their manager Jeanette Wall to write a response that, Hopkins says, wouldn’t antagonize the accusers. They would end up posting two statements on Facebook page. In the first, dated May 11, Hopkins and Bruce said they were trying to address the allegations against Ben “with openness and accountability,” later writing, “Our primary goal here is to ensure that a survivor of abuse has a voice, that their story should be heard and that people who cross the line should be held accountable.”

In the May 18 Facebook entry, Hopkins indicated that they knew who the accuser was. “While I am open to understanding this person’s perspective, I strongly contest the account put forth in Jezebel, read their statement but stopped short of an unequivocal denial that would have contradicted PWR BTTM’s message that the safety of its fans was paramount. “That being said,” the post concluded, “in keeping with my commitment to my principles, I believe it is my responsibility to be accountable to this individual’s perspective and to honor it accordingly.”

“I was catatonic at this point” and “didn’t contribute much” to the statement,” Hopkins says of its mixed message. “I was just sort of reading and approving things.”

The Facebook posts seemed to frustrate the band’s followers and fuel their detractors. More than 1,400 people commented on the posts. “There is literally no proof either way [at the moment] so talking utter shite in the comment section trying to discredit this band is equally groundless,” wrote one. Responded another: “just because it hasnt been public doesnt mean there isnt proof! haha lol.”

Billboard’s numerous, repeated attempts to present the accounts of these accusers as well as those of the music-industry representatives that dropped PWR BTTM were met largely with silence. The person who leveled the charges of sexual abuse did respond by email, but after expressing anger that Billboard was working on a story about Hopkins, declined to speak on the record.

Cordero-Kolin did not respond to emails and voicemails. Polyvinyl president and co-founder Matt Lunsford said in a statement, “All matters between Polyvinyl and PWR BTTM were amicably resolved in August 2017,” when the label allowed Bruce and Hopkins, with the help of an attorney, to buy the rights to Pageant. The band’s former lawyer, Jeff Koenig, did not respond, nor did former manager Jeanette Wall, former agent Josh Lindgren or Jessi Frick, founder of indie label Father/Daughter, which put out PWR BTTM’s 2015 album Ugly Cherries.

Bruce also chose not to comment. Hopkins and Bruce fell out in 2017, because, Hopkins says, Bruce talked to Hopkins’ accuser at one point without telling his then bandmate. Hopkins felt betrayed, but says today: “I’m not here to drag Liv Bruce. She was in a really hard situation.” Barbaris, when asked what the chances were of PWR BTTM getting back together, says, “They discussed it, but we have to get through this first. We’ve got to see where Liv’s head is in a year or two.”

The rest of the acts that dropped off of PWR BTTM’s ill-fated 2017 tour wouldn’t comment — with the exception of Zach Burba of Seattle’s iji. “It was confusing and disappointing and it just didn’t seem like the tour could go forward with all of the things people were saying,” he says, adding, “I felt then, as I do now, that the best move was to simply listen to what people were saying.”

‘Every Allegation Needs to Be Looked at Seriously and Critically’

Thanks in large part to the #MeToo movement, which was founded by activist Tarana Burke in 2006 (and went viral in 2017 when actress Alyssa Milano began using it as a hashtag for her tweets about Harvey Weinstein), accusations of sexual abuse and predatory behavior increasingly provoke civil lawsuits, criminal investigations, and survivors going on the record with the backing of friends and family.

The allegations against Hopkins come with no such documentation, but as Debra Katz — the attorney who represented Brett Kavanaugh accuser Christine Blasey Ford and works on other prominent #MeToo cases ― points out, “People don’t typically lie about these allegations.” If it happens, she says, it happens in “a very small percentage of cases.”

“Every allegation needs to be looked at seriously and critically,” says Katz, although she adds that it’s very difficult for journalists to write about anonymous allegations. “It puts you in a pretty hard place. You have [one] person saying this stuff happened and [the other] denying it, and you can’t quite adjudicate it.”

‘That Sounds Like The Name of Your Record’

Hopkins returned to Brooklyn on July 4, 2017, and reluctantly adjusted to life beneath the radar. They live with a girlfriend, Phoebe Herland, who, like Bruce, Hopkins met at Bard. They worked for a catering company and as a bartender at a favorite local club. Hopkins is the Dungeon Master for a weekly Dungeons & Dragons group, which also serves as a sort of support group, encouraging Hopkins to write new songs.

“I believe Ben. Of course I believe Ben. I wouldn’t be friends with Ben if I didn’t believe them,” says Shelby, one of Hopkins’ fellow Dungeons & Dragons players, who asked that her last name not be used. “When a group of people operate in a groupthink way, things can get out of hand. I’m just so sad that it happened to Ben.”

Hopkins, who wears a red D&D T-shirt and 10-sided-dice earrings during one of the Skype sessions, says the games, which have continued during the pandemic, are therapeutic and led to the title of the album. “‘I held my breath for a really long time once’ was something I said while playing and everybody said, ‘That sounds like the name of your record, given what you’ve been through,” says Hopkins.

Asked what Hopkins hopes the album will accomplish, the singer-songwriter stares off camera for a long time. “I was expunging so much pain in that music,” they say finally. “I hope it makes people feel less alone.”