Following our Billboard staff-picked list of the 100 greatest songs of 2000, we’re writing this week about some of the stories and trends that defined the year for us. Here, we look back at a relatively sunny, tranquil period in country music history — before Nashville, like the rest of the world, was changed by global events the following year.

In the fall of 1999, Warner Bros. signee and former professional wrestler Chad Brock released a cover of Hank Williams, Jr.’s “A Country Boy Can Survive.” As this point, he was a known Nashville quantity, having reached No. 3 on the Hot Country Singles & Tracks chart with “Ordinary Life” in April.

The song boasted some heavy hitters: George Jones and Bocephus himself sang a few lines. And it had a decent news peg: Brock appended “(Y2K Version)” to the title and updated the lyrics. (Opening couplet: “Computer man says it’s the end of time/ December 31st, nineteen ninety-nine.”) Despite all this, the song stalled out at No. 30, six slots below what Jones mustered six years before with “High-Tech Redneck.”

That same year, a woman contacted Brock. She was living in his old apartment and was still getting his mail. So he swung by, and a few minutes of small talk turned into hours of conversation; they got married a few months later. With the help of Jim Collins and Stephony Smith, Brock turned the story into a song. Released in February 2000, “Yes!” topped the country singles chart for three weeks in June. A sprightly midtempo strummer, “Yes!” is a sort of proto-Swiftian narrative, teetering on self-reference (“She moved into my old apartment/ That’s how we got this whole thing started”) and reveling in a sense of romantic destiny.

This was the prevailing mode of country music in 2000. Like a bottle of André fresh out the cooler, it was sparkling and domestic. In a year light on superstar releases, a combination of newcomers, B-listers and old reliables offered a vision of country as viewed from a front-porch rocking chair rather than a barstool. It was the year of Lee Ann Womack’s first No. 1, and Kenny Rogers’s last.

And as a year, it felt a little like 1999, Part 2. The three top-selling albums of 2000 were Faith Hill’s Breathe (released in November of 1999), Dixie Chicks’s Fly (August of ‘99), and Shania Twain’s Come On Over (November of… ‘97). Two of the three acts had chart-topping singles on Billboard‘s Country Songs listing in 2000: the Chicks with the tall-grass fantasia “Cowboy Take Me Away,” and Hill with “The Way You Love Me,” a pure pop number about consciousness transference. Neither of Twain’s 2000 singles placed better than #17; to be fair, they were her already 16x-platinum-certified album’s eleventh and twelfth singles.

Hill’s success hewed to the Twain model: Breathe was a big-tent pop record with drawl. “The Way You Love Me” even had a pneumatic intro and scrambled vocals out of the playbook of Twain’s then-creative partner, Mutt Lange. “You’re bringing out the Elvis in me,” sang Hill on one album cut — and sure enough, she scored with ballads, and she scored with pop/rock that found her both struck by love and free to examine it at every angle.

The only other solo country artist working with this kind of verve, conceivably, was LeAnn Rimes, for whom the Coyote Ugly soundtrack was a kind of extended play. The album, frontloaded by four new Rimes songs (produced by Trevor Horn, lip-synced by Piper Perabo), led the Top Country Album chart for six straight weeks. Country programmers, though, were cooler to Rimes’s adventures in modern recording: “Can’t Fight the Moonlight” layered an R&B-indebted vocal sense over Max Martin-style keyboard hits (and a killer feint of a hard-rock intro); the public took it to No. 11 on the Hot 100, but stalled out at No. 61 on country radio.

The job of placing R&B on country radio, then, fell to Mark Wills. On Permanently, his third record, he spun two R&B covers into hits. The big single was Brian McKnight’s high-concept piano ballad “Back at One,” which Wills took to No. 2 in March. it’s easy, of course, to make the sturdy bones of “One” dance. The degree of difficulty was upped slightly with Wills’ take on Brandy’s “Almost Doesn’t Count.” Perhaps his camp took note of the the Brandy video, in which she wears a cowboy hat in the back of a pickup. No matter: he jettisons a typically elegant Fred Jerkins III arrangement — all wind chimes and stuttering hi-hat — and installs a lonesome mandolin, amping the tension until he’s suddenly singing a power ballad.

Other balladeers — other than Billy Ray Cyrus, whose LA/Nashville hybrid “You Won’t Be Lonely Now” could’ve been a mainstream rock hit in previous years — kept things in a calmer register. There was “The Chain of Love” by Clay Walker, a brush-heavy take on the then-raging Pay It Forward craze. There was “We Danced” by Brad Paisley, a meet-cute that (like “Yes!”) revolved around one party trying to claim property from another. The fiddle wags like dinner-table entertainment; Paisley sings without the twinkle that would be as much his trademark as hotshot solos.

There was also Kenny Rogers’s “Buy Me a Rose,” a rare indie offering on the charts. He argues — forcefully, gently — for small gestures; country listeners rewarded him in a big way, making him the oldest artist to reach No. 1. Featured on the track was Alison Krauss, who also provided backing vocals that year for John Michael Montgomery’s own final No. 1, the mawkish, gruesome “The Little Girl.” Just like All-4-One did for two of Montogomery’s previous country chart-toppers, Luther Vandross later released his own version of “Buy Me a Rose” on his final album, 2003’s Dance With My Father.

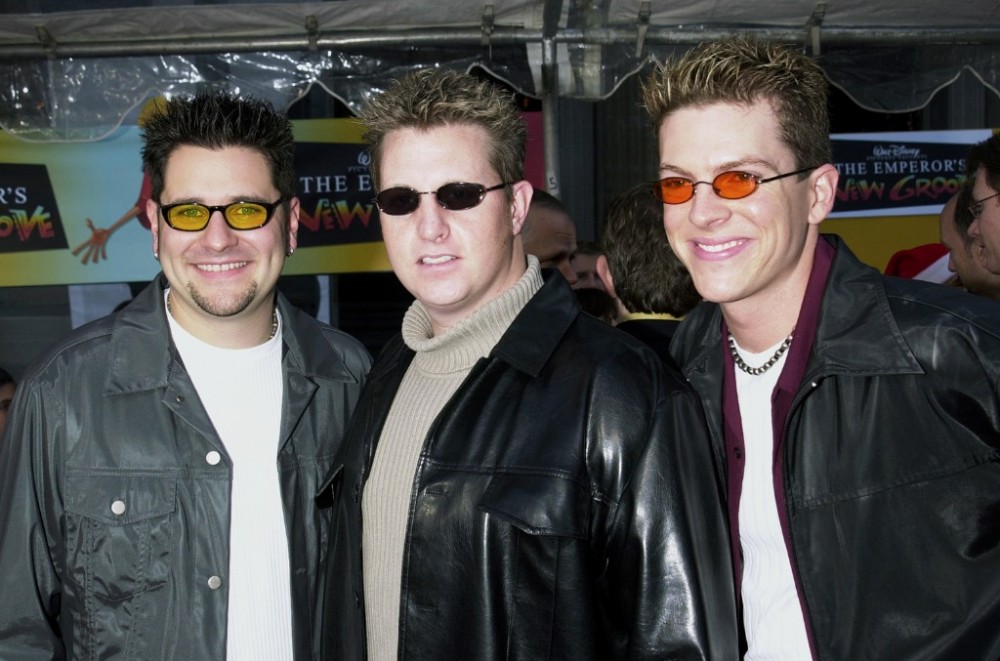

But there was no bigger or better country ballad in 2000 than Lee Ann Womack’s “I Hope You Dance,” featuring Sons of the Desert (who contained two Womacks, brothers to each other but not to Lee Ann). Like Dylan’s “Forever Young” or Rascal Flatts’s “My Wish,” it is a checklist of hopes — and as such reveals as much about the singer’s regrets, possibly, as their love. The Sons make this explicit in their counter-melodic responses, and it’s always gutting. A wedding-reception staple to this day, “Dance” reached No. 14 on the Hot 100, and was — this beggars belief — Womack’s only country No. 1.

At the upper reaches of the country charts, 2000 was better than most for women. Thanks in huge part to Fly, women had the No. 1 country album for 42 weeks (if Coyote Ugly counts as a Lee Ann Rimes record, which, why not). In 1999, 18 weeks saw a woman credited on the No. 1 country single; that number jumped to 22 in 2000. In 2001, there were ten such weeks; in 2002, there were three. The picture holds focus when considering total spins: a study from February of this year indicated that women’s 33% of total spins in 2000 was actually a high-water mark; last year they logged half that much.

Promoters and programmers alike are still hashing out the assumptions and biases that affect radio play for women (to say nothing of performers who aren’t white, who are non-binary, and so on). But one contributing factor may have been 9/11, and the way country decided which and whose reactions were ble. Largely, they belonged to men: Alan Jackson, Toby Keith, Darryl Worley. Aaron Tippin dropped a patriotic co-write from his 2000 release People Like Us; within a week after the towers fell, he was in a studio tracking “Where the Stars and Stripes and the Eagle Fly.” That patriotic salute was an emotional ocean away from his 2000 hit “Kiss This,” a throwback line-dancer about a cheating partner being dommed in public. At the end of 2002, the Dixie Chicks issued “Travelin’ Soldier,” a story-song about the Vietnam war that gave voice to contemporary fears – at least until the next year’s country-radio boycott.

A few months before “Soldier,” Phil Vassar followed up his smash debut with “American Child,” the lead single for the album of the same name. It’s a typically lovely, piano-driven waltz. There’s a closing reference to a grandfather who died in World War II, but the bulk of it expresses an awestruck belief in exceptionalism: America’s, and Vassar’s, and Vassar’s daughter. It was of a piece with 2000’s “Just Another Day in Paradise,” which found him practically yelping with joy at stacks of bills and busted washing machines. And “Paradise” positioned Vassar as a worthy successor to Vince Gill, who raised his own romantic ruckus on the No. 6 hit “Feels Like Love.”

Even the breakups left a sweet taste in the mouth. Rascal Flatts introduced themselves on No. 3 debut “Prayin’ For Daylight” with a smidgen of showoff close harmony. The narrator is holed up in a dark bedroom, wondering if his lover will return, but the song’s unhurried jangle and moseying fiddle give the impression of a dog waiting for his person to get home from work. The week after a remixed “Amazed” garnered them a Hot 100 No. 1 — still the last country song to top the chart, outside of a post-pop Taylor Swift — Lonestar topped the Country Songs chart with “Smile,” a classic grit-and-grin farewell ballad. Travis Tritt took hat in hand for the second-chance swayer “Best of Intentions,” his last No. 1 to date.

But the best goodbye tune, perhaps, was Alan Jackson’s No. 6 hit “www.memory.” Sure, the URL doesn’t resolve — but the sentiment does. The singer genially directs his ex to a digital shrine, anticipating the profile creeping of the oncoming social-media age. “You won’t even have to hold me or look into my eyes,” he croons, “You can tell me that you love me/ Through your keyboard and wires.” It was, essentially, “Someday (Y2K Version).” The mixture of wistfulness and wryness was typical of Jackson. The kindness and twinkle were typical of what made the country music audience of 2000 say yes!