With Goldman Sachs predicting recorded-music revenue will reach $75 billion in 2030, investors want in.

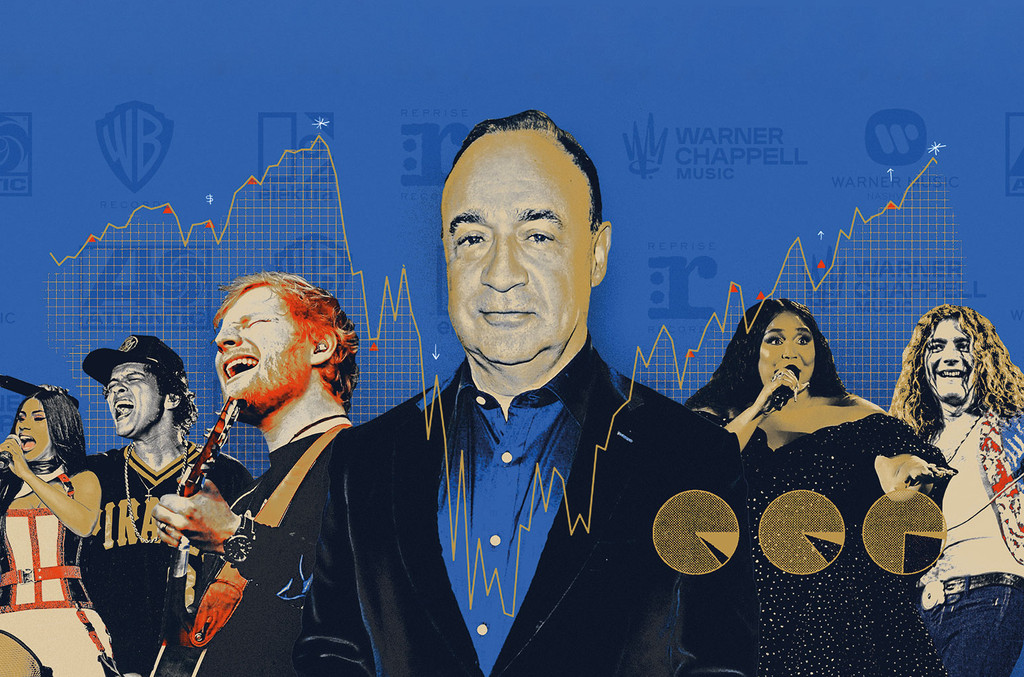

On June 3, Warner Music Group went public in the year’s biggest stock offering, and its share price rose 39% over the next two days. The company itself didn’t raise any money — the shares were sold by Len Blavatnik‘s conglomerate, Access Industries — but it’s now worth $18.3 billion based on its $31.05 per share closing price on June 10.

After selling $1.86 billion in stock and adding dividends and management fees, Access has taken out $3.34 billion from Warner — slightly more than the $3.3 billion Blavatnik bought the company for in 2011.

More important, WMG’s initial public offering marks the music industry’s triumphant return to Wall Street after years spent searching for a sustainable business model. The last recorded-music company to be publicly traded was also Warner Music, which Edgar Bronfman Jr. and a group of investors bought from Time Warner in 2004 for $2.6 billion and floated on the New York Stock Exchange the following year, in a bell-ringing ceremony that featured Led Zeppelin guitarist Jimmy Page playing the riff from “Whole Lotta Love.”

At the time, the hot new technology was ringtones, and global recorded-music revenue was still plummeting — it declined 27.8% from $20.5 billion in 2004 to $14.8 billion in 2011, when Blavatnik’s Access bought Warner. Since then, global recorded-music revenue has risen 36.5% to $20.3 billion, while Warner’s value has risen 455%. The biggest change may have been optimism about the future of streaming.

That optimism is radically reshaping assumptions about the value of music assets. Six months ago, industry observers questioned whether Chinese technology giant Tencent had overspent by committing to buy a 10% stake in Universal Music Group for $3.3 billion in a deal that valued the entire company at an eye-popping $33 billion. When the deal closed, that valuation was 24.9 times UMG’s 2019 earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization.

Judging by Warner’s value after its first four days of trading, however, one could make the case that Tencent might actually have underpaid. Warner’s enterprise value peaked at 26.8 times its trailing 12-month EBITDA of $755 million ($34.76 per share on June 5), which could set a tone for future deals that a major music company can be worth 20 to 25 times EBITDA — on par with most public entertainment companies, according to data gathered by New York University finance professor Aswath Damodaran. (It was reported that Tencent planned to be an anchor investor in Warner, with a 10% stake in the IPO.)

In the bleak days, when Access bought Warner at a price-to-EBITDA ratio of 9.6 — and even when Warner bought Parlophone Records at a ratio of 7.4 in 2013 — investors had little interest in recorded music and publishing. Now, with Goldman Sachs predicting recorded-music revenue will be worth $75 billion in 2030 — a 12% compound annual growth rate — investors want in.

Other investors might feel Warner’s potential is limited because it’s so tightly controlled (Blavatnik still owns 81% if the underwriters exercise their option of the publicly traded Class B shares, which have 99% of the voting rights), and some institutional investors aren’t interested in companies where they can’t influence management. While Access cashed out 15% of its equity and the IPO didn’t raise money for Warner, “that might be a minor quibble,” not a red flag, says Hal Vogel, a longtime music industry analyst who runs Vogel Capital Management. Over the long term, he says, “the industry has turned upward, and I don’t see any real problems for the business model going forward.”

Warner’s stock offering comes as outrage mounts over police brutality and social injustice — on June 2, a day before the IPO, Warner canceled business as usual to support #TheShowMustBePaused, whose founders note the recorded-music industry was built largely by black artists. (Many of those artists were ripped off by labels, and there have been calls to pay them or their families back royalties as reparations.) On June 3, Warner and Blavatnik’s foundation announced they would donate $100 million to support social justice and fight racism.

Warner could also be hurt by the continuing pandemic. In May, the company said its revenue in April fell nearly 12% to $294 million from $335 million in the prior year. During financial roadshows for potential investors leading up to the IPO, Warner didn’t project economic performance for 2020 and instead forecast the company will produce $1 billion in EBITDA in 2021, according to sources.So far, at least, Warner’s immediate future looks secure. As of March 31, it had $484 million in cash and cash equivalents and $300 million in an untapped revolving credit facility. Its EBITDA is high enough to make Warner one of the few public companies that plans to continue paying out dividends during the financial downturn.

During Warner’s roadshow, management also told investors it plans to focus on profit margin, according to a Wall Street analyst familiar with Warner. While the company’s operating income before depreciation and amortization was $625 million in the year ended Sept. 30, 2019 — which gives it a margin of 13.9% — it plans to become more circumspect about making investments. However, its next quarterly earnings report — expected in July — will show a one-time, $400 million expense related to a change in accounting for share-based compensation.

Given the enthusiasm for music stocks, investors are likely to shrug off such a paper loss, according to the analyst. “These investors will want to hold for long term — some of them feel it is at least a $40 stock,” says the analyst. “They are betting on a secular growth story from the industry.”

A version of this article originally appeared in the June 13, 2020 issue of Billboard.